Optimizing Ruby's JSON, Part 5

In the previous post, we showed how we eliminated two malloc/free pairs of calls

when generating small JSON documents, and how that put us ahead of Oj when reusing the JSON::State object.

But that API isn’t the one people use, so if we wanted to come out ahead in the micro-benchmarks users might perform themselves, we had to

find a way to get rid of that JSON::State allocation too, or to somehow make it faster.

Typed Data

Because that JSON::State allocation, isn’t just about any allocation. In Ruby, everything is an object, but not all objects are created equal.

In previous parts I touched on how some objects aren’t actually allocated, and called “immediates”, I also touched on how core objects like String and

Array have both “embedded” and “heap” representations.

JSON::State is a type defined in C from the extension, using the TypedData API. Peter Zhu has a great blog post that goes in-depth into

how these work and how to use them, but I’ll offer a quicker explanation here.

To define a custom object type, you start by defining a C structure that holds the type metadata:

static const rb_data_type_t JSON_Generator_State_type = {

"JSON/Generator/State",

{

.dmark = State_mark,

.dfree = State_free,

.dsize = State_memsize,

.dcompact = State_compact,

},

0, 0,

RUBY_TYPED_WB_PROTECTED | RUBY_TYPED_FREE_IMMEDIATELY | RUBY_TYPED_FROZEN_SHAREABLE,

};You can read Peter’s post if you want to know all the juicy details, but in short, it’s a collection of flags and callbacks to instruct the GC

on how to deal with this object. For instance State_mark allows the GC to list all the references this object has to other objects.

And then you define an allocator function, that will replace the default Class#allocate method for that class when you register it with rb_define_alloc_func:

static VALUE cState_s_allocate(VALUE klass)

{

JSON_Generator_State *state;

VALUE obj = TypedData_Make_Struct(

klass,

JSON_Generator_State,

&JSON_Generator_State_type,

state

);

state->max_nesting = 100;

state->buffer_initial_length = FBUFFER_INITIAL_LENGTH_DEFAULT;

return obj;

}

// snip...

void Init_generator(void)

{

mJSON = rb_define_module("JSON");

VALUE mExt = rb_define_module_under(mJSON, "Ext");

VALUE mGenerator = rb_define_module_under(mExt, "Generator");

cState = rb_define_class_under(mGenerator, "State", rb_cObject);

rb_define_alloc_func(cState, cState_s_allocate);

}The TypedData_Make_Struct macro takes care of allocating a 40B object slots of type T_DATA, as well as to call ruby_xcalloc(sizeof(JSON_Generator_State))

so we have some heap memory to store the object state.

The difference between calloc and malloc, is that when you use malloc, the memory that is allocated for you is left as is, with whatever data was

in it when it was last freed. Whereas calloc will do some extra work to fill that memory with zeros.

The struct used to interpret the content of the 40B slot is RTypedData defined in rtypeddata.h:

struct RTypedData {

struct RBasic basic;

const rb_data_type_t *const type;

const VALUE typed_flag;

void *data;

};| flags | klass | type | typed_flag | *data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x0c | 0xffeff | 0xbbbef | 0x1 | 0xcccdef |

As for the JSON_Generator_State struct, it’s a simple struct holding our configuration, for a total of 72B on 64-bit platforms:

typedef struct JSON_Generator_StateStruct {

VALUE indent;

VALUE space;

VALUE space_before;

VALUE object_nl;

VALUE array_nl;

long max_nesting;

long depth;

long buffer_initial_length;

bool allow_nan;

bool ascii_only;

bool script_safe;

bool strict;

} JSON_Generator_State;With this explanation, you may have understood that it’s not a simple object allocation we’re dealing with, but a noticeably more expensive operation. This can be easily confirmed by profiling yet again:

require "json"

i = 20_000_000

data = [1, "string", { a: 1, b: 2 }, [3, 4, 5]]

while i > 0

i -= 1

JSON.generate(data)

endIf we consider the cost of the object slot allocation, plus the heap allocation, and also the extra cost of Ruby’s GC having to call

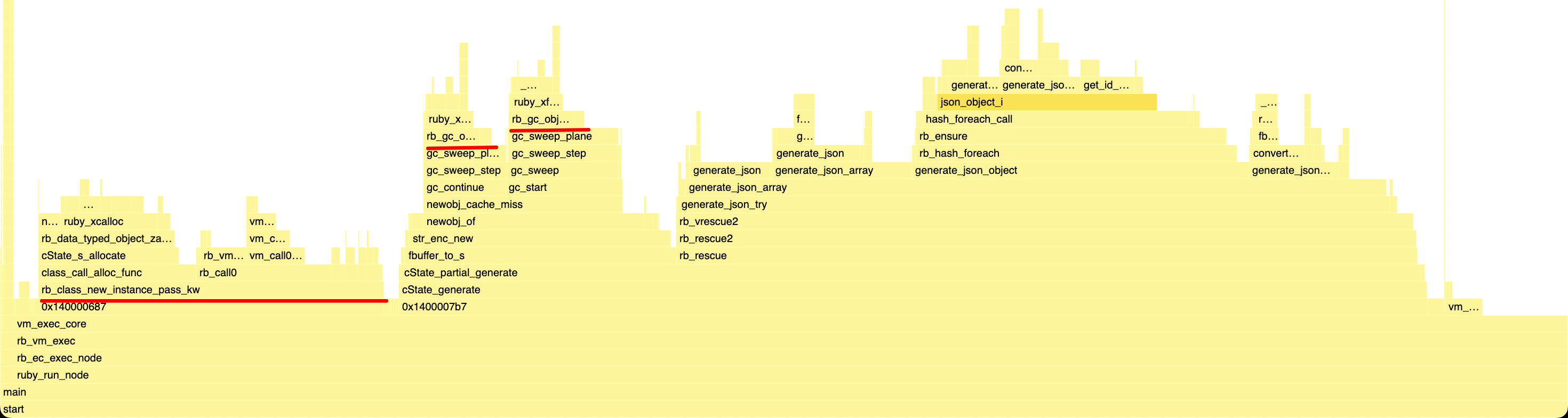

ruby_xfree when these objects are garbage collected, it all amounts to practically 30% of the overall runtime, which is massive:

In addition, you can see inside rb_class_new_instance_pass_kw that we’re spending quite a bit of time inside rb_call0.

That’s because when you call .new on a Ruby class, it pretty much works like this:

class Class

def new(...)

instance = allocate

instance.send(:initialize, ...)

instance

end

endBut as of Ruby 3.4, this logic is implemented in C, so it can’t benefit from an inline cache and other niceties, instead, it has to rely on the Global Call Cache Cache Table, but also forwards arguments from C, which isn’t the most efficient.

That’s why Aaron Patterson has been trying to reimplement Class#new in Ruby, but it’s not quite ready yet.

Embeding RTypedData

As you might have noticed on the flame graph, allocating the object slot really is the least of our problems, it’s really the heap allocation and

deallocation that’s impacting performance very negatively.

Given that the existing API somewhat imposes a JSON::State allocation, if we can’t eliminate it, we can instead try to make it cheaper.

Since our JSON_Generator_State is only 72B, with the extra 32B imposed by RTypedData it could theoretically fit in a 160B slot,

which would be perfect.

Back in 2023, I paired with Peter on allowing TypedData objects to be embeded,

and we used that new capability to embed various core classes, the most notable one being Time, and it

did almost cut the cost of Time.now in half:

| |compare-ruby|built-ruby|

|:-----------------------|-----------:|---------:|

|Time.now | 12.150M| 22.025M|

| | -| 1.81x|

|Time.now(in: "+09:00") | 3.545M| 4.794M|

| | -| 1.35x|

So embedding JSON::State would be a big win with very little effort.

I’d just need to add RUBY_TYPED_EMBEDDABLE in the JSON_Generator_State_type, and remove the ruby_xfree call in State_free, and that’s it,

the setup cost would be cut in half.

Except there was one problem: we never made RUBY_TYPED_EMBEDDABLE a public API, as we thought it might be too easy to shoot yourself in

the foot with it, and we didn’t want to expose the C API users to a whole new class of hard-to-understand crashes.

Embedded objects are hard to use from C because, since Ruby 2.7, Ruby’s GC is capable of compacting the heap, which means moving live objects from one slot to another. So when working in C with an embedded object, you have to be very careful not to hold onto a native pointer that is pointing inside the object slot, because if the GC moves the object, the pointer you previously got is now pointing inside a totally different object, which can cause all sorts of memory corruption issues, and from experience these are among the hardest bugs to investigate and fix.

Maybe we should still expose this API, it could definitely lead to some nice performance gains for some native gems, but that requires some careful considerations, and would take time. When I was working on this patch, we were already almost in November, way too late in the Ruby release cycle to hope to get a decision before the Ruby 3.4 release.

So that wasn’t a viable option, I needed to find another solution.

Using a T_OBJECT

That’s where I thought about using a “regular” object, AKA a T_OBJECT. That’s the internal type of all the objects you define in pure Ruby,

and as long as you define all the instance variables in the initialize method, they’re pretty much guaranteed to be embedded too.

After all, I recently moved the State#configure method from C into Ruby, I could go further and turn

JSON::State into a PORO. That would for sure make it much faster to allocate and initialize, plus it would benefit from JIT, and would allow sharing

more code with the JRuby and TruffleRuby implementations of JSON.generate.

But while the instantiation would get faster, access to the JSON::State fields from C would get slower, and that is for two reasons.

First, all the native fields in the struct, like long depth, would now need to be boxed (I explained what it means in part 3).

So that means some small overhead for every access, but it would probably be negligible.

The real problem would be uncached instance variable lookups. Because to look up an instance variable, just like for methods, you need quite a bit of work. Here again, you can check my previous post on Object Shapes to understand why.

When that lookup is done from Ruby code, we benefit from inline caches, so most of the time it’s just an integer comparison to revalidate the cache, and then a simple memory read at an offset.

But when looking up the instance variables of an object from C extensions, the only possible API is rb_ivar_get, so that means no inline caches.

Contrary to uncached method lookups, you have no equivalent to the Global Call Cache Cache Table for instance variables, you have to go through a

full lookup every time. It’s less expensive than for a method, but still, you have to walk up the shape tree, so that’s potentially a lot of pointer

chasing.

If there was a C API to do cached instance variable lookups, I think using a T_OBJECT would have been a great solution, but since it isn’t

the case, I quickly gave up on the idea, it wasn’t even worth prototyping and profiling, and I 100% expected it not to perform well enough.

I also quickly considered using a Ruby Struct class, as those aren’t T_OBJECT but T_STRUCT, they’re also embedded, but the position of each

member is stored in an Array, so in some cases, it can be a bit faster to look up uncached, but I wasn’t hopeful it would move the needle enough.

Reusing State

If I couldn’t make the allocation faster, another avenue would be to find a way to reuse the object.

Technically, the JSON::State is mutable, and the various #to_json methods are free to add arbitrary fields into it, like some sort of Hash,

as a way to pass information around. But in practice, no-one really uses that, so I was OK with considering such a minor breaking change.

But a bigger challenge was JSON’s global configuration.

If you look at the JSON.generate method:

def generate(obj, opts = nil)

if State === opts

state = opts

else

state = State.new(opts)

end

state.generate(obj)

endIt would be easy to avoid allocating a new State object when opts is nil and instead use a single immutable State object.

That would definitely speed up JSON.generate enough to get ahead on all or at least most micro-benchmarks.

But even though the benchmarks inside ruby/json call JSON.generate, a lot of code out there, and presumably other people’s benchmarks might just as

well call JSON.dump, and in such case, opts wouldn’t be nil, but set to JSON.dump_default_options or another Hash derived from it, hence that

optimization would be out the window pretty quickly.

I toyed with various ideas on how I could detect changes to JSON.dump_default_options to keep a cached JSON::State object around,

but that’s not realistic because it defaults to a mutable hash, so I’d need to monkey-patch dozens of methods to be notified when it is mutated.

As a side note, I really hate JSON.dump_default_options. It’s really not a good idea to

globally change how a library behaves like this, as the various other libraries that depend on the json gem likely don’t expect it at all.

I’d like to deprecate it for the next major version, but we’ll see.

Lazy Allocation

At that point, I had been thinking about this problem for a few days, with no real solution in sight, until it hit me: the JSON::State only needs to be

allocated if a #to_json method has to be called, and it’s not that frequent.

If you are using some serialization framework in the style of Active Model Serializers, it most likely already converts all objects that don’t directly

map to a JSON type into some more primitive Ruby objects that are serializable without having to call #to_json on them.

Similarly, if you use Rails JSON rendering, likely via something like render json: obj, it first converts the given object tree into primitive types,

so here again, #to_json calls are unlikely.

Overall, if #to_json needs to be called, we’re likely not in a situation where that one extra allocation will make a measurable difference.

But even if we don’t need to allocate the JSON::State instance, we still need to have some memory somewhere for a JSON_Generator_State struct,

because our C code needs to be able to check the configuration somehow.

Since it’s only 72B, it can very comfortably fit in the C stack, making it close to free.

The downside though, is that the State#configure method we moved from C to Ruby in part two,

well it had to go back to C.

I was a bit sad, but as we say here, sometimes you need to take a step back in order to take a big jump forward.

The next step was to introduce a new internal API to allow to bypass State#generate, so that JSON.generate was now:

def generate(obj, opts = nil)

if State === opts

opts.generate(obj)

else

State.generate(obj, opts)

end

endBy calling into a class method, we don’t require the allocation.

For the pure-Ruby version of the generator, it didn’t change much, as there would be no way to elide the allocation, so I implemented

JSON::Pure::State.generate in a fairly obvious way:

module JSON

module Pure

module Generator

class State

def self.generate(obj, opts = nil)

new(opts).generate(obj)

end

end

end

endFor the C extension, this allowed to allocate the JSON_Generator_State on the stack:

static VALUE cState_m_generate(VALUE klass, VALUE obj, VALUE opts)

{

JSON_Generator_State state = {0};

state_init(&state);

configure_state(&state, opts);

char stack_buffer[FBUFFER_STACK_SIZE];

FBuffer buffer = {0};

fbuffer_stack_init(&buffer, state.buffer_initial_length, stack_buffer, FBUFFER_STACK_SIZE);

struct generate_json_data data = {

.buffer = &buffer,

.vstate = Qfalse,

.state = &state,

.obj = obj,

.func = generate_json,

};

rb_rescue(generate_json_try, (VALUE)&data, generate_json_rescue, (VALUE)&data);

return fbuffer_to_s(&buffer);

}If you are unfamiliar with the state = {0}; syntax, it’s asking the compiler to zero out the memory it allocated on the stack, because otherwise

our struct would just be initialized with whatever was left on the stack, which isn’t great.

The other important thing to notice here is the struct generate_json_data, which is defined as this:

struct generate_json_data {

FBuffer *buffer;

VALUE vstate;

JSON_Generator_State *state;

VALUE obj;

generator_func func;

};That structure isn’t new, it was there before the patch, but you can notice it has both JSON_Generator_State *state, in other words, a pointer

to the struct holding our configuration, and VALUE vstate which is a reference to the TypedData that holds the pointer.

It’s a bit of a duplication, but that avoids some pointer chasing every time the code needs to check if some configuration flag is set.

The vstate used to be initialized to self, but now we initialize it to Qfalse, which conceptually is the global reference to Ruby’s singleton

false object. But in practice false is an immediate, and simply 0.

With that in place, I could then implement the lazy initialization. A lot of internal functions used to receive the vstate as an argument, and in C

arguments are passed by copy, so if I wanted to lazily allocate the State object, it had to be passed by reference instead.

In short, it meant changing the signature of many functions like this:

- static void generate_json_integer(FBuffer *buffer, VALUE Vstate, JSON_Generator_State *state, VALUE obj)

+ static void generate_json_integer(FBuffer *buffer, struct generate_json_data *data, JSON_Generator_State *state, VALUE obj)And then change the one place where we call #to_json, to use a new vstate_get helper:

- tmp = rb_funcall(obj, i_to_json, 1, Vstate);

+ tmp = rb_funcall(obj, i_to_json, 1, vstate_get(data));Which is in concept very similar to the class memoization pattern in Ruby:

static void vstate_spill(struct generate_json_data *data)

{

VALUE vstate = cState_s_allocate(cState);

GET_STATE(vstate);

MEMCPY(state, data->state, JSON_Generator_State, 1);

data->state = state;

data->vstate = vstate;

}

static inline VALUE vstate_get(struct generate_json_data *data)

{

if (RB_UNLIKELY(!data->vstate)) {

vstate_spill(data);

}

return data->vstate;

}As always, C code makes it a bit cryptic, but you should be able to recognize the memoization pattern in vstate_get.

As for vstate_spill, spilling is a term often used when moving data from registers onto the RAM because it can’t fit there anymore.

Similarly here, we’re “spilling” the JSON_Generator_State struct from the stack onto the heap.

We also update the data->state pointer, so that if the #to_json method we called mutate the configuration,

it’s immediately reflected (but please don’t do this, I beg you).

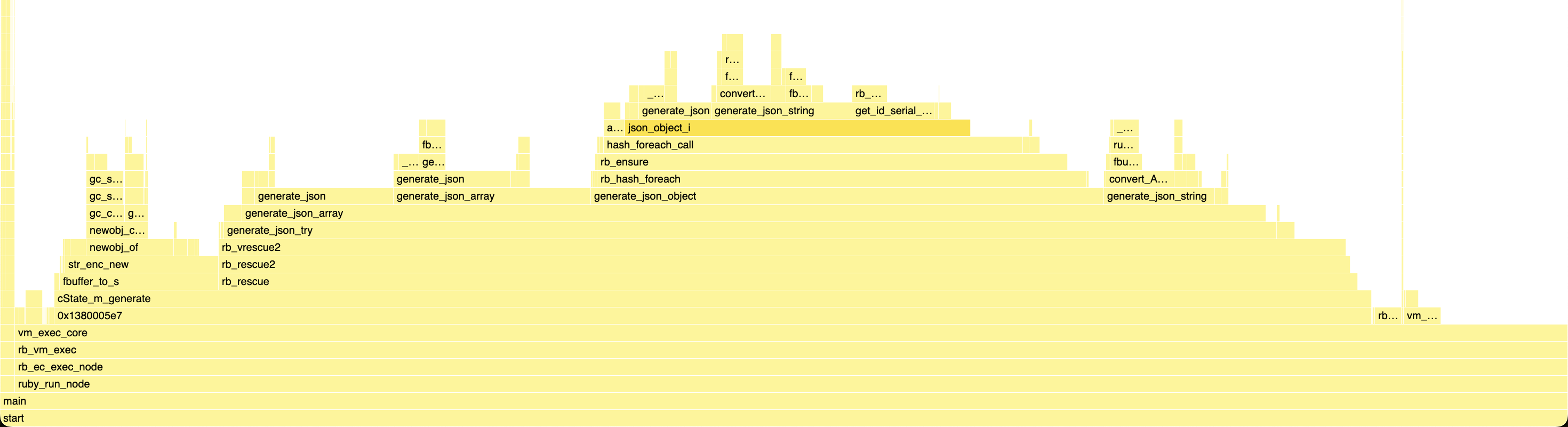

As predicted by the flame graph, avoiding this allocation had a massive impact on micro-benchmarks:

== Encoding small mixed (34 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 506.104k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 5.389M (± 0.2%) i/s (185.57 ns/i) - 27.330M in 5.071556s

Comparison:

before: 3113113.5 i/s

after: 5388830.4 i/s - 1.73x faster

Enough of a jump that JSON.generate performance was now almost on par with re-using the JSON::State object, and a bit ahead of Oj

== Encoding small mixed (34 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

json 613.914k i/100ms

json (reuse) 624.068k i/100ms

oj 545.935k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

json 6.550M (± 0.1%) i/s (152.67 ns/i) - 33.151M in 5.061360s

json (reuse) 6.667M (± 0.1%) i/s (149.99 ns/i) - 33.700M in 5.054534s

oj 5.822M (± 0.1%) i/s (171.76 ns/i) - 29.480M in 5.063498s

Comparison:

json: 6549898.9 i/s

json (reuse): 6667228.7 i/s - 1.02x faster

oj: 5822168.8 i/s - 1.12x slower

And now, the setup cost was finally almost invisible on the flame graph:

To Be Continued

This was the final optimization done to the generator worth detailing here.

Hence, I can finally start talking about the parser in the next part.

I think I’ll only need two, maybe three parts for the parsing side.

Edit: Part 6 is here.