Optimizing Ruby's JSON, Part 4

In the previous post, we established that as long as ruby/json wasn’t competitive on

micro-benchmarks, public perception wouldn’t change. Since what made ruby/json appear so bad on micro-benchmarks was its setup cost, we had to

find ways to reduce it further.

Spot the Seven Differences

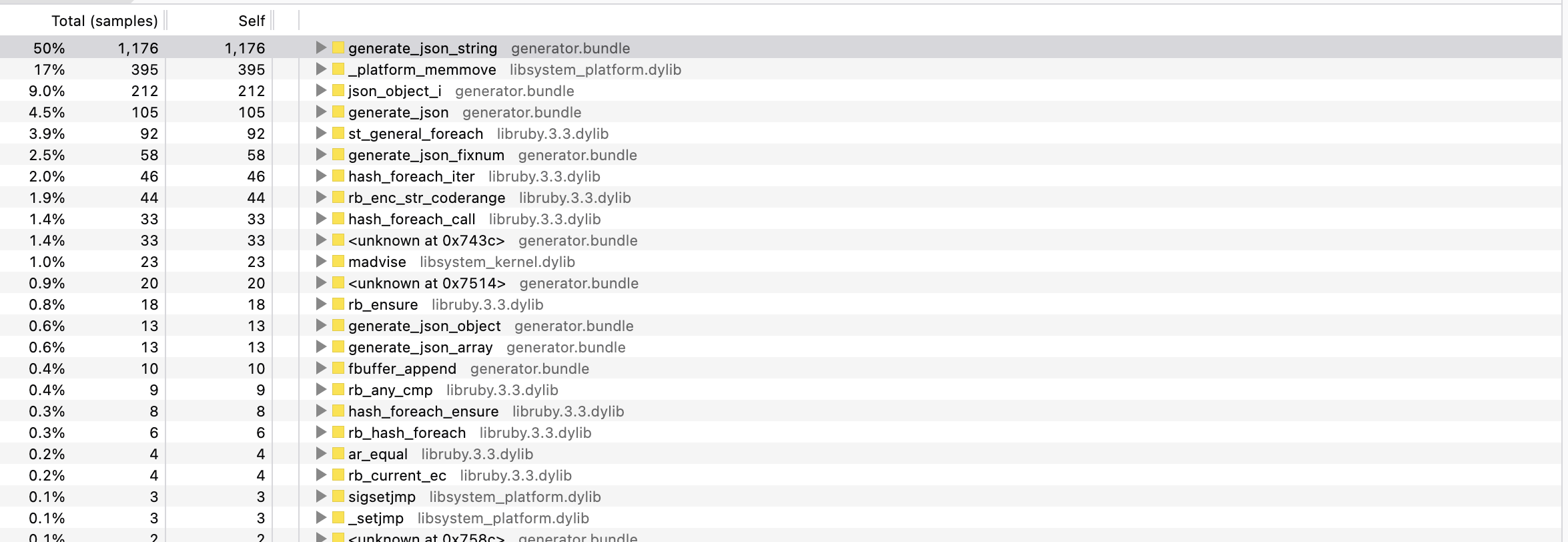

So I decided to file this performance discrepancy as a bug, and investigate it as such and started

profiling Stephen’s micro-benchmark with both ruby/json and oj:

benchmark_encoding "small mixed", [1, "string", { a: 1, b: 2 }, [3, 4, 5]]As mentioned in previous parts, I expected the extra allocation would be the main issue, and that re-using the JSON::State object would

put us on par with Oj, but it’s always good to revalidate our assumptions:

== Encoding small mixed (34 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

json (reuse) 467.051k i/100ms

json 252.570k i/100ms

oj 529.741k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

json (reuse) 4.857M (± 1.9%) i/s (205.88 ns/i) - 24.287M in 5.001995s

json 2.689M (± 0.5%) i/s (371.86 ns/i) - 13.639M in 5.071865s

oj 5.860M (± 0.6%) i/s (170.65 ns/i) - 29.665M in 5.062753s

Comparison:

json (reuse): 4857171.1 i/s

oj: 5859811.8 i/s - 1.21x faster

json: 2689181.9 i/s - 1.81x slower

Even without that extra allocation, we were still 20% slower, that was unexpected, and should be fixed before exploring ways to eliminate the State allocation.

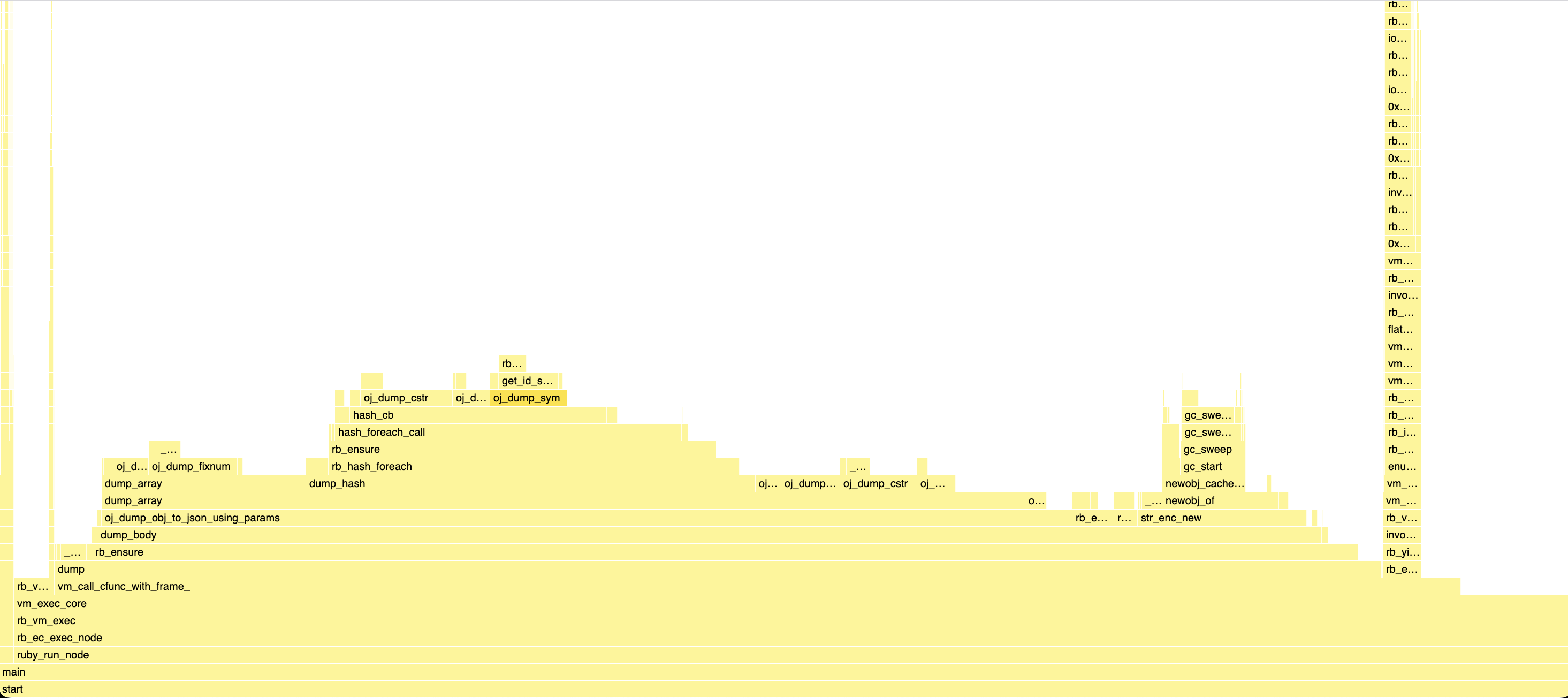

As always, this meant profiling, but this time I profiled both ruby/json and Oj to see where the difference might be:

require "json"

i = 20_000_000

data = [1, "string", { a: 1, b: 2 }, [3, 4, 5]]

state = JSON::State.new

while i > 0

i -= 1

state.generate(data)

endrequire "oj"

Oj.default_options = Oj.default_options.merge(mode: :compat)

i = 20_000_000

data = [1, "string", { a: 1, b: 2 }, [3, 4, 5]]

while i > 0

i -= 1

Oj.dump(data)

endOnce I got the two profiles, it was a matter of playing “Spot the seven differences”.

Something that jumped to me quite quickly, is that on that micro-benchmark, even though we’re re-using our JSON::State object,

we still spend a significant amount of time allocating and freeing our internal buffer. Still, on the Oj profile, there wasn’t

any malloc or free call. This suggested that Oj re-used a persistent buffer across calls or allocated it on the stack.

A quick investigation of Oj’s source code confirmed it was the latter:

typedef struct _out {

char stack_buffer[4096];

char *buf;

char *end;

char *cur;

// ...

} *Out;

// ...

/* Document-method: dump

* call-seq: dump(obj, options={})

*

* Dumps an Object (obj) to a string.

* - *obj* [_Object_] Object to serialize as an JSON document String

* - *options* [_Hash_] same as default_options

*/

static VALUE dump(int argc, VALUE *argv, VALUE self) {

struct dump_arg arg;

struct _out out; // Stack allocation

struct _options copts = oj_default_options;

// ...

}Stack and Heap

Since this post is intended for people not necessarily familiar with C, I need to explain a bit what the stack and the heap are. This is just meant as a quick introduction.

The heap is most of the RAM available on your system, if you need memory to store some data, you call malloc(number_of_bytes)

and get a pointer back that is at least as big as the number of bytes you asked for, and once you are done with it you call free(pointer).

There are many different allocators (e.g. jemalloc, tcmalloc), using various algorithms and techniques to keep track of which memory is used and

how large each allocated chunk is, but even with the best allocators, malloc and free are somewhat costly. In addition, if you don’t know upfront

how much memory you actually need, you might need to call new_pointer = realloc(pointer, new_size) to allocate a larger chunk and copy the content

over and free the old chunk, this is fairly expensive.

And for Ruby C extensions specifically, you generally don’t use malloc / free / realloc, but ruby_xmalloc / ruby_xfree / ruby_xrealloc,

which are wrappers around the standard functions which additionally update Ruby GC statistics, so that the GC can trigger after some

threshold is reached which can further increase the cost of heap allocations.

On the other hand, the stack is a memory region that’s preallocated for each native thread, and that is used to store the current state of a function,

such as local variables while calling another function. For instance, if you have a function f with two int64_t local variables a and b,

a will be stored at stack_pointer + 0 and b at stack_pointer + 8. And if f calls into another function f2, the stack pointer will be

incremented by 16 before entering f2, and restored back to its previous value when returning from f2.

This makes stack allocations essentially free, at least compared to heap allocations, and it’s almost guaranteed data stored there will be in the CPU cache as it’s a very “hot” memory region.

But stack allocation isn’t a silver bullet, first because whenever you return from the function that memory should be considered freed, so in many

cases that’s not suitable. You can also not resize (realloc) it from a callee function.

Additionally, the stack is limited in size.

On most modern UNIX-like systems you got a fairly generous 8MiB of stack space for the main thread, but only 1MiB on Windows.

And most systems give less stack space to additional threads, for instance, Alpine Linux which uses the musl libc only gives

128kiB of stack space to additional threads, which really isn’t a lot. That’s why it’s not rare for Ruby C extension maintainers

to get Alpine-specific bug reports.

Stack Allocated Buffer Struct

So stack allocations should be used carefully and reasonably, the conventional wisdom being to not allocate more than 1kiB on the stack, and to only

do it in leaf functions (that don’t call any other functions), or functions that only call into a few known functions.

In our case, the JSON::State#generate method isn’t a leaf function, and might call into arbitrary Ruby code if it needs to call #to_json or

#to_s on an object, so 4kiB seemed a bit excessive to me, but still, we could use stack allocations reasonably to gain some performance.

ruby/json wasn’t just doing one malloc+free call, but two. The first one in cState_prepare_buffer allocates the FBuffer struct, which

contains the buffer metadata, such as its capacity:

typedef struct FBufferStruct {

unsigned long initial_length;

char *ptr;

unsigned long len;

unsigned long capa;

} FBuffer;That struct being just 32B large, it makes a lot of sense to allocate it on the stack, which would save a pair of malloc+free calls,

and only increase the stack size by a negligible amount.

You can see the diff, it’s not complicated but requires a lot of small changes across the

codebase. Additionally, since the parser also used FBuffer, it had to be modified too to embed the FBuffer struct inside the JSON_ParserStruct

instead of just keeping a pointer.

The gains were pretty good for such a small change:

== Encoding small mixed (34 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 265.435k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 2.831M (± 1.2%) i/s (353.28 ns/i) - 14.333M in 5.064502s

Comparison:

before: 2630445.8 i/s

after: 2830628.7 i/s - 1.08x faster

But still not enough.

Efficient Integer Printing

Before continuing on reducing the setup cost, another thing that surprised me on that profile was the 3.6% spent in fltoa.

Not that 3.6% is anywhere near a hotspot, but that’s a bit much for such a simple function.

If you are not familiar with C naming conventions, you may wonder what this function is doing. In the C standard library you have

several functions to parse strings as various integer types, such as atoi, atol, and atoll, for int, long and long long

respectively. Why ato? Because these functions assume a stream of ASCII encoded bytes1, hence “ASCII to int” -> atoi. That’s also probably

where the Ruby #to_i method got its name from.

So here, fltoa is a long to ASCII conversion function, and f is just the namespace for the fbuffer.h file.

Let’s have a look at how it is done:

static void freverse(char *start, char *end)

{

char c;

while (end > start) {

c = *end, *end-- = *start, *start++ = c;

}

}

static long fltoa(long number, char *buf)

{

static char digits[] = "0123456789";

long sign = number;

char* tmp = buf;

if (sign < 0) number = -number;

do *tmp++ = digits[number % 10]; while (number /= 10);

if (sign < 0) *tmp++ = '-';

freverse(buf, tmp - 1);

return tmp - buf;

}

static void fbuffer_append_long(FBuffer *fb, long number)

{

char buf[20];

unsigned long len = fltoa(number, buf);

fbuffer_append(fb, buf, len);

}There’s something quite odd here. First, we allocate a 20B buffer on the stack, write the number in reverse in the buffer, reverse the string

and finally copy the stack buffer onto the output buffer.

In Ruby, it would look like:

DIGITS = ('0'..'9').to_a

def fltoa(number)

negative = number.negative?

number = number.abs

buffer = "".b

loop do

buffer << DIGITS[number % 10]

number /= 10

break if number.zero?

end

buffer << "-" if negative

buffer.reverse!

buffer

endWriting the number in reverse can be a useful trick if you are appending it to an existing buffer of dynamic length because you don’t know upfront how long the number will be nor where the buffer ends.

But here we’re writing inside a stack buffer of known size and then copying the result, so it’s a bit wasteful.

Instead we can write in the stack buffer backward, starting from the end of the buffer, and save on having to reverse the digits at the end.

static long fltoa(long number, char *buf)

{

static const char digits[] = "0123456789";

long sign = number;

char* tmp = buf;

if (sign < 0) number = -number;

do *tmp-- = digits[number % 10]; while (number /= 10);

if (sign < 0) *tmp-- = '-';

return buf - tmp;

}

#define LONG_BUFFER_SIZE 20

static void fbuffer_append_long(FBuffer *fb, long number)

{

char buf[LONG_BUFFER_SIZE];

char *buffer_end = buf + LONG_BUFFER_SIZE;

long len = fltoa(number, buffer_end - 1);

fbuffer_append(fb, buffer_end - len, len);

}Here again, it’s a small optimization on a very specific part of the generator, so I crafted a micro-benchmark to see if it had the expected benefits:

benchmark_encoding "integers", (1_000_000..1_001_000).to_a== Encoding integers (8009 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 9.770k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 97.929k (± 0.9%) i/s (10.21 μs/i) - 498.270k in 5.088542s

Comparison:

before: 88309.9 i/s

after: 97928.6 i/s - 1.11x faster

Not bad, probably will only be noticeable for documents containing lots of large integers, but also a very simple optimization.

This can probably be optimized further by writing directly in the output buffer so that we don’t need to copy, and maybe even use log to

compute upfront how many digits the number has, but that was good enough for now, so I went back to reduce setup cost.

Using an RString as Buffer

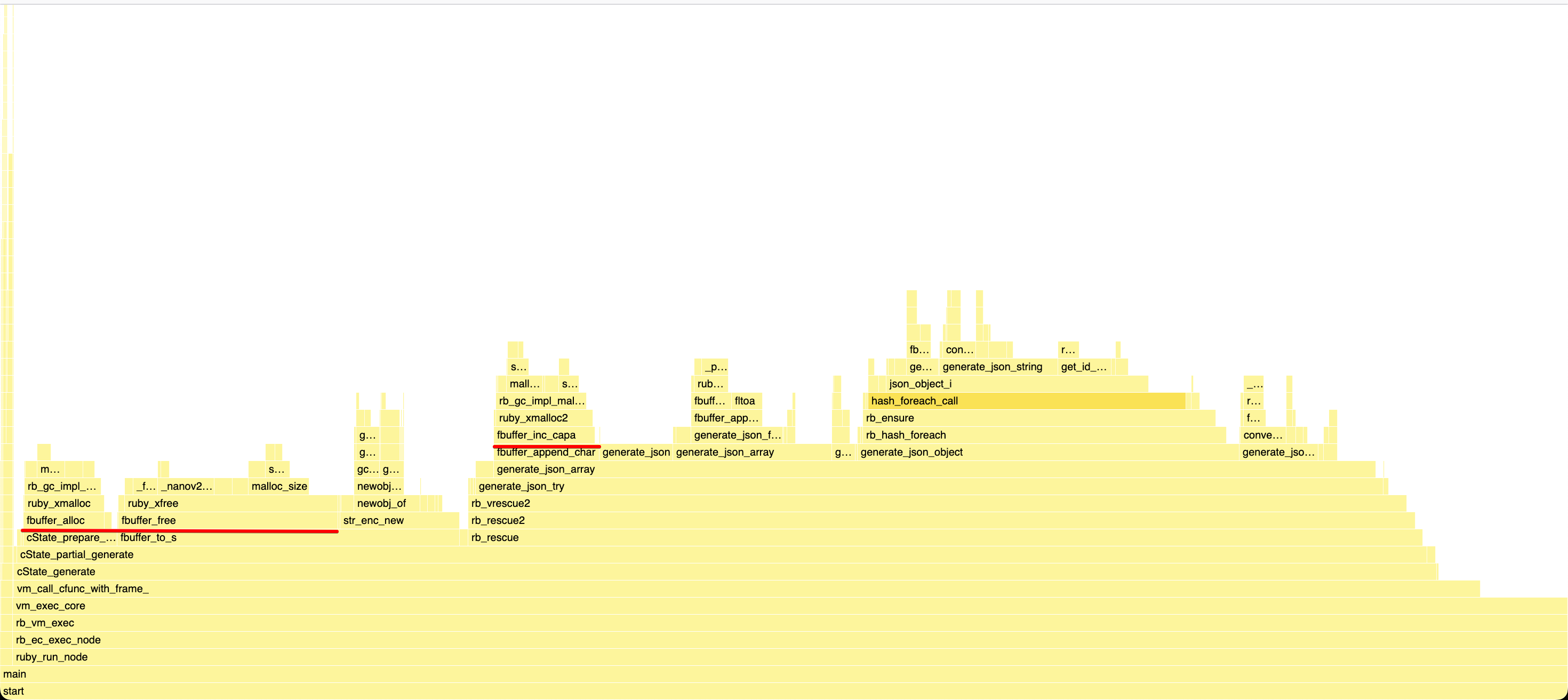

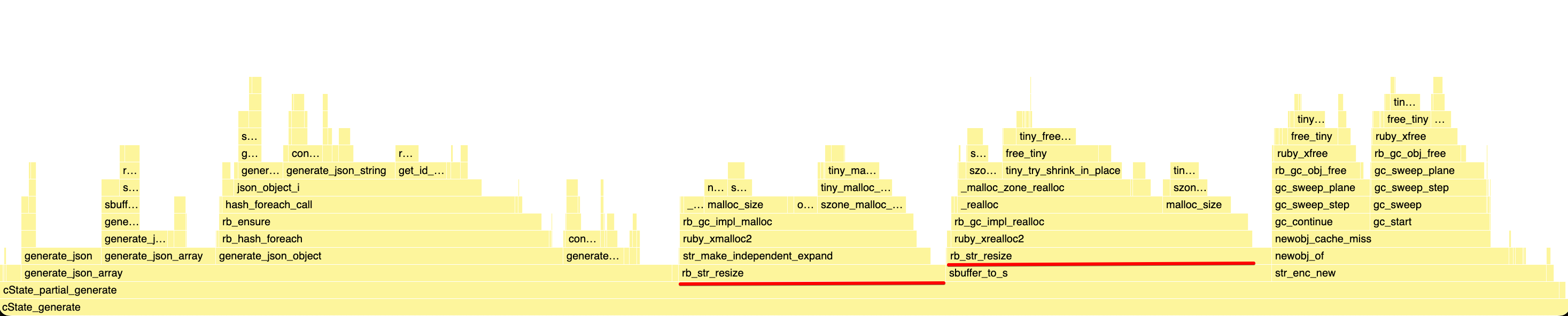

So I went to profile Stephen’s micro-benchmark again:

As you can see, we’re now calling malloc and free half as much, but still 100% more than Oj, and once we’re done filling our buffer,

we copy all its content in another memory region managed by Ruby when calling str_enc_new (actually rb_utf8_str_new, but the profiler doesn’t see it because of inlining).

On micro-benchmarks the copy is negligible, but on larger ones like twitter.json, it can amount to as much as 4% of the overall runtime:

The cost of allocating the String object is close to invisible compared to the copy.

So at that point, you are probably wondering why not simply directly use the Ruby String as our buffer. We would let Ruby manage the memory right from the start, save the copy, and for micro-benchmarks, we’d probably fit inside an embedded String (more on that later). We also wouldn’t have to be extra careful to free our internal buffer in case an exception is raised, so it would eliminate many potential sources of memory leaks.

That’s not exactly a novel idea, there are a bunch of methods inside Ruby itself that do that exact thing, like Time#strftime,

and I had prototyped it a couple of month prior during a pairing session

with Étienne Barrié.

So I went on to reimplement that again, given so much had changed since then that rebasing would have been harder.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t the win you could expect, quite the opposite:

== Encoding small mixed (34 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 208.242k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 2.201M (± 1.0%) i/s (454.41 ns/i) - 11.037M in 5.015727s

Comparison:

before: 2648506.5 i/s

after: 2200665.8 i/s - 1.20x slower

== Encoding twitter.json (466906 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 205.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 2.065k (± 1.5%) i/s (484.37 μs/i) - 10.455k in 5.065262s

Comparison:

before: 2099.6 i/s

after: 2064.5 i/s - same-ish: difference falls within error

It didn’t move the needle on real-world benchmarks, and noticeably degraded performance on micro-benchmarks.

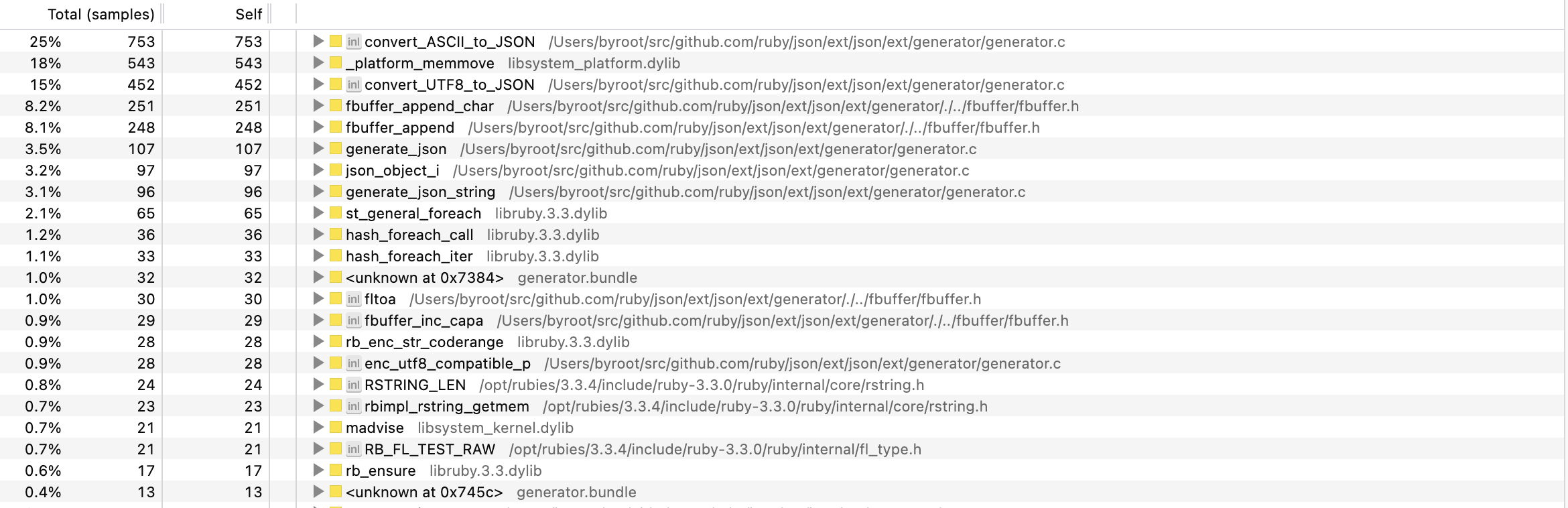

Why did it end up slower? The answer is it depends. When resizing a Ruby String, Ruby doesn’t simply call realloc like ruby/json

does for its raw buffer, it also calls malloc_usable_size,

or the platform equivalent, malloc_size on macOS

or _msize on Windows.

void *

rb_gc_impl_realloc(void *objspace_ptr, void *ptr, size_t new_size, size_t old_size)

{

// snip...

old_size = objspace_malloc_size(objspace, ptr, old_size);

TRY_WITH_GC(new_size, mem = RB_GNUC_EXTENSION_BLOCK(realloc(ptr, new_size)));

if (!mem) return mem;

new_size = objspace_malloc_size(objspace, mem, new_size);

// snip...

objspace_malloc_increase(objspace, mem, new_size, old_size, MEMOP_TYPE_REALLOC);

return mem;

}This again is to keep the GC statistics up to date and give the opportunity to the GC to trigger if some threshold is hit.

Something I wonder though, and that I ought to investigate, is that rb_gc_impl_realloc is provided with the known old_size

and new_size. Sometimes it’s 0 when the called doesn’t know what the size was, but for strings, I believe it does, and yet

data information is simply ignored unless no malloc_usable_size is available:

static inline size_t

objspace_malloc_size(rb_objspace_t *objspace, void *ptr, size_t hint)

{

#ifdef HAVE_MALLOC_USABLE_SIZE

return malloc_usable_size(ptr);

#else

return hint;

#endif

}Just like malloc / free etc, the performance of malloc_usable_size varies a lot depending on the allocator, I haven’t benchmarked

on Linux, nor with jemalloc, so it’s possible that this overhead would have been negligible there, and that may be why Ruby doesn’t try to skip

that call when possible?

But as mentioned at the end of the last post, we’re here to change perception, so we have to be faster on the machines users are more likely to use

for benchmarking, and that includes macOS with the default allocator.

In hindsight, there’s something else I could have done to make using a Ruby string as a buffer faster:

diff --git a/ext/json/ext/generator/generator.c b/ext/json/ext/generator/generator.c

index da78fe1..effc8cc 100644

--- a/ext/json/ext/generator/generator.c

+++ b/ext/json/ext/generator/generator.c

@@ -1024,8 +1024,8 @@ static VALUE cState_partial_generate(VALUE self, VALUE obj)

{

GET_STATE(self);

- VALUE string = rb_utf8_str_new(NULL, 0);

- rb_str_resize(string, state->buffer_initial_length - 1);

+ VALUE string = rb_str_buf_new(state->buffer_initial_length - 1);

+ rb_enc_associate_index(string, utf8_encindex);

SBuffer buffer = {

.capa = state->buffer_initial_length - 1,

.str = string,== Encoding small mixed (34 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 290.040k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 3.127M (± 0.3%) i/s (319.84 ns/i) - 15.662M in 5.009436s

Comparison:

before: 2616126.5 i/s

after: 3126563.7 i/s - 1.20x faster

== Encoding twitter.json (466906 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 202.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 2.049k (± 2.9%) i/s (488.12 μs/i) - 10.302k in 5.032888s

Comparison:

before: 2114.5 i/s

after: 2048.7 i/s - same-ish: difference falls within error

Quite a nice gain for such a small change, and you may wonder what’s so different about these two lines of code.

Variable Width Allocation and Embeded Objects

When Ruby allocates an object, it doesn’t call malloc like a C program would.

Instead, it asks the GC for what’s called a “slot”, which means a fixed-size memory region inside a memory page

managed by the GC.

Up until the introduction of Variable Width Allocation by Peter Zhu and

Matt Valentine-House in Ruby 3.2, all Ruby slots were of the same size: 40B.

You might wonder, how can all objects be of the same size if you are able to create strings or arrays of arbitrary size?

That’s because many of the Ruby core types, like String, Array etc, have multiple internal representations.

To stick with the String example, here is a simplified version of what its layout looks like in rstring.h:

struct RString {

struct RBasic {

VALUE flags;

VALUE klass;

} basic;

long len;

union {

struct {

char *ptr;

long capa;

} heap;

struct {

char ary[1];

} embed;

} as;

};If you are unfamiliar with C’s union, it means that the struct can contain either of its sub structs.

To better visualize, here’s how Ruby stores the "Hello World" string:

| flags | klass | length | *ptr | capa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x000234 | 0xffeff | 11 | Hello Wo | rld\0 |

Each column is 8 bytes wide, or 64 bits, the first 8 bytes are used to store the object flags, we touched on those before, the following 8 bytes are used to store a pointer to the object class, and then the last 24 bytes are used to store the string content inside the object slot.

So you can deduce that strings can be as long as 16 ASCII characters, or rather 15 because you need one byte to store the terminating NULL byte.

Perhaps you’ve read in the past about this limit, and remember that it was 23 characters. That was true but was recently changed by Peter

because it required packing the embedded length inside the flags bitmap instead, which made things slower. That’s your classic memory usage vs execution speed tradeoff.

Now if we try to append content to that string, and go past the embedded capacity, say, 200 characters long, it will call malloc(201), store the string content inside

that malloced region and the object slot will look like this instead:

| flags | klass | length | *ptr | capa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x000234 | 0xffeff | 200 | 0xbbbef | 200 |

But with the introduction of Variable Width Allocation, slots are still fixed-sized in a way, but there are now multiple sizes: 40, 80, 160,

320 and 640. A slot can’t grow in size, so in the above scenario where we appended to a string, nothing changes, Ruby will still have to “spill”

the content on the string on the heap by calling malloc.

However, if we ask Ruby upfront for a larger string, it will make sure to allocate a larger slot for it if that allows it to be embedded.

In the diff above I call rb_str_buf_new(state->buffer_initial_length - 1) or rb_str_buf_new(511), so on Ruby 3.2+, Ruby will allocate a 640B

wide slot for us, allowing us to store up to 640 - 24 - 1 = 615 bytes before having to spill on the heap, and given our micro-benchmark only needs 34B

it means no malloc nor free call for the buffer, only a Ruby object slot allocation, which is way cheaper in most cases.

Since we’ll need to ask Ruby to allocate us an object slot so we can return a String object, we might as well ask for a larger one in case we can

fit in it. If the cost for a 40B or 640B slot is the same, might as well get the bigger one.

In addition to saving on the malloc call, we also save on the free call. When GC triggers and there’s no longer any reference to that slot, Ruby

will just mark the slot as available.

But I didn’t think of this at that time, so maybe that’s something I’ll need to revisit in the future.

Be Nice To Your Mother

Instead I resigned myself to using a stack allocation for the buffer content too.

But I went with a much more conservative size than Oj, a mere 512B.

The implementation is rather simple, I simply had to add one extra type field inside the FBuffer struct

to keep track of the buffer provenance, so that we behave a bit differently inside fbuffer_inc_capa if the buffer is on the stack.

Here’s the implementation with some extra comments:

static inline void fbuffer_inc_capa(FBuffer *fb, unsigned long requested)

{

if (RB_UNLIKELY(requested > fb->capa - fb->len)) {

unsigned long required;

if (RB_UNLIKELY(!fb->ptr)) {

fb->ptr = ALLOC_N(char, fb->initial_length);

fb->capa = fb->initial_length;

}

for (required = fb->capa; requested > required - fb->len; required <<= 1);

if (required > fb->capa) {

if (fb->type == STACK) {

// If the buffer is on the stack

const char *old_buffer = fb->ptr;

// We allocate a larger buffer on the heap

fb->ptr = ALLOC_N(char, required);

// Mark it as now being on the heap

fb->type = HEAP;

// Copy the old content over

MEMCPY(fb->ptr, old_buffer, char, fb->len);

} else {

REALLOC_N(fb->ptr, char, required);

}

fb->capa = required;

}

}

}This had the expected effect on micro-benchmarks, a nice 7% improvement:

== Encoding small mixed (34 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 286.112k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 3.024M (± 0.7%) i/s (330.67 ns/i) - 15.164M in 5.014435s

Comparison:

before: 2836034.1 i/s

after: 3024200.8 i/s - 1.07x faster

However, I quickly noticed that it also became way slower on real-world benchmarks:

== Encoding twitter.json (466906 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 156.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 1.572k (± 1.7%) i/s (636.13 μs/i) - 7.956k in 5.062686s

Comparison:

before: 2134.0 i/s

after: 1572.0 i/s - 1.36x slower

While I was determined to spend a lot of effort in improving ruby/json performance on micro-benchmarks, degrading its performance

on real-world benchmarks was a huge red line for me, so I had to figure out what happened.

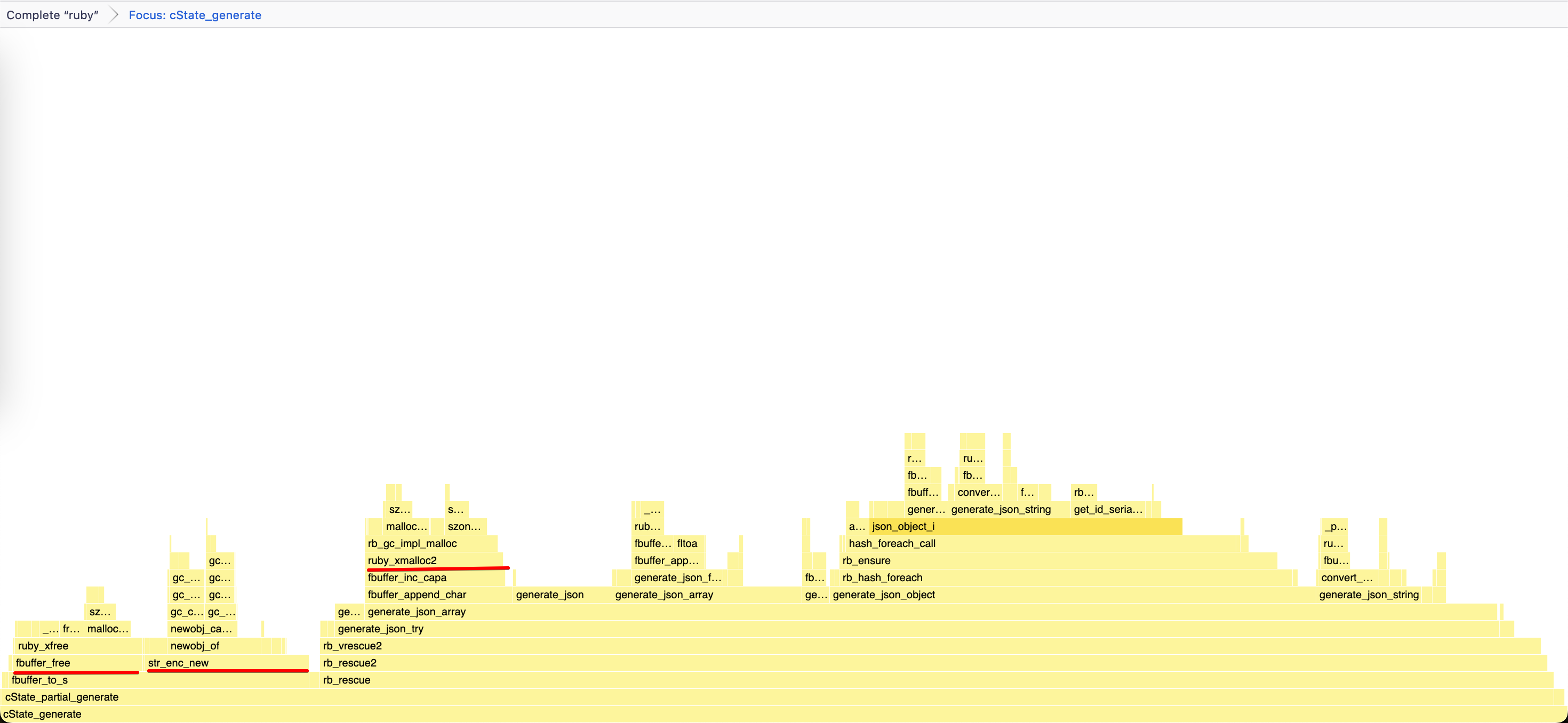

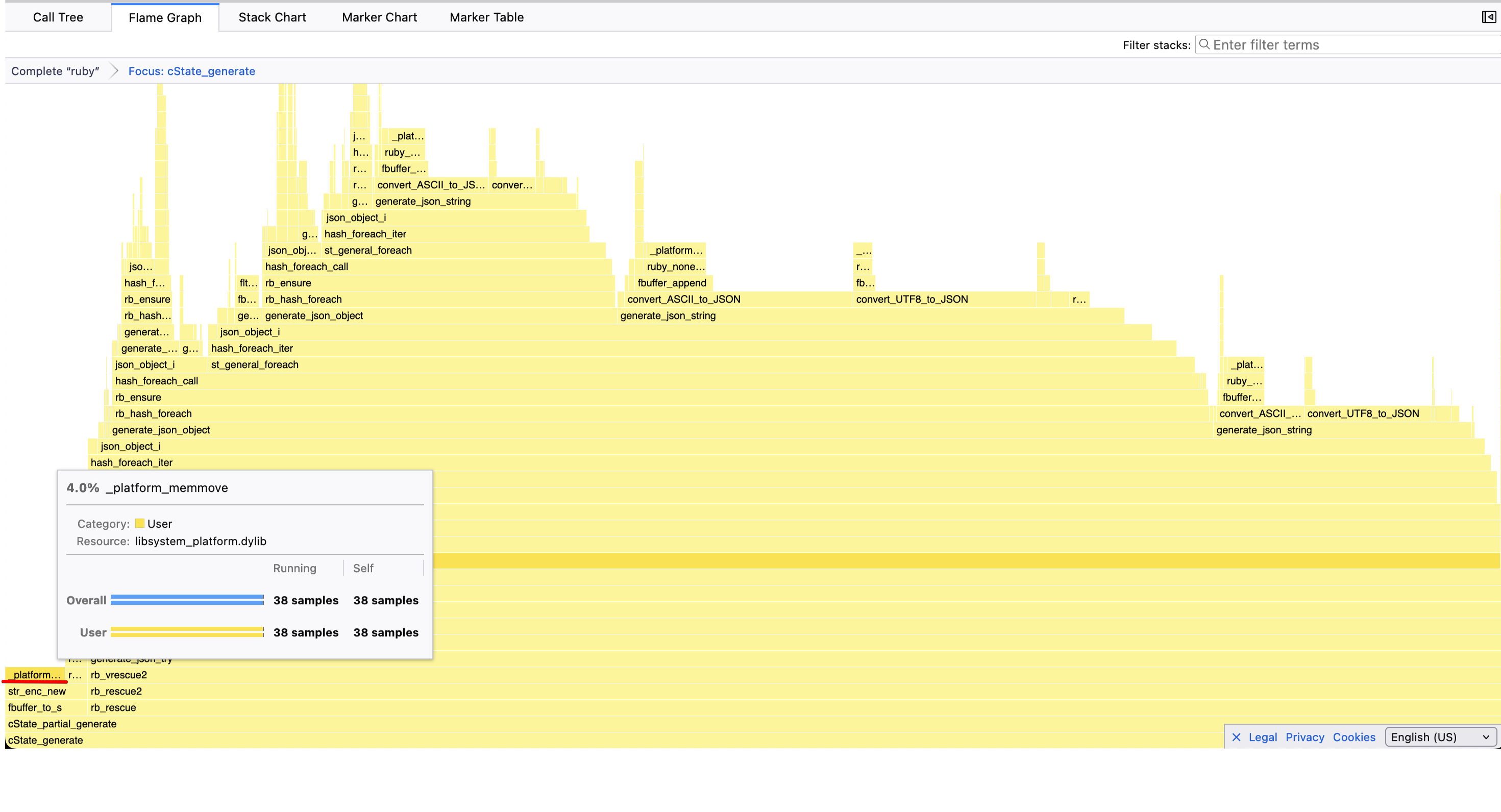

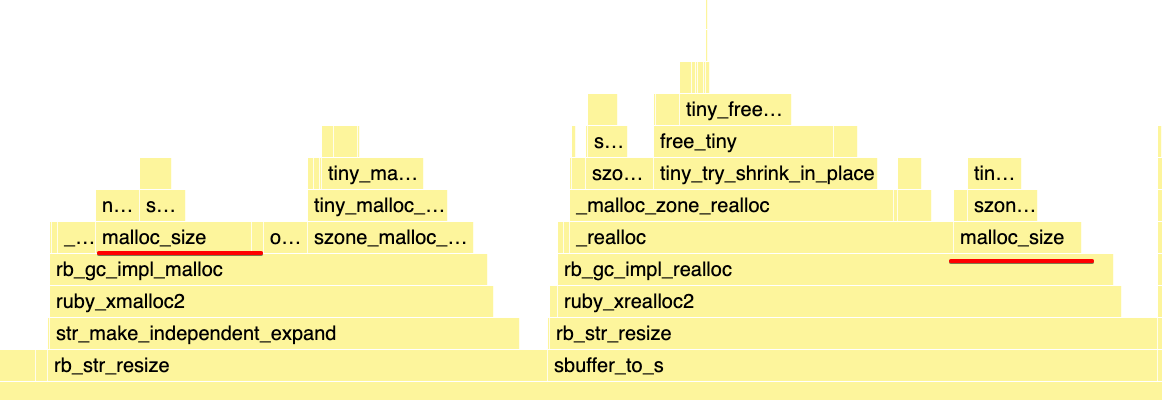

So I went back to my profiler, and started playing “Spot the seven differences” again:

Before:

After:

It’s far from obvious if you don’t know what to look for, but you can see that before we were spending 50% of the runtime in generate_json_string, and afterward, only 3.1%

and instead, the top was trusted by a bunch of smaller functions called by generate_json_string.

These are the signs of what is sometimes referred to as “the mother of all optimizations”: inlining.

Even in C, calling a function isn’t that cheap. It’s cheap enough that you generally don’t think about it but costly enough that you try to minimize function calls in hotspots.

You can do that by refactoring your code to use bigger functions, or even copying code around using macros, but that gets old quickly. Instead, the compiler does that for us, it identifies the small leaf functions that aren’t worth calling and instead copies its content inside the parent, even if it means copy-pasting it dozens and dozens of times. In addition to saving on the overhead of a function call, it also allows to optimize the caller and callee together, sometimes allowing to eliminate redundant computations or simply dead code.

That’s what the inline keyword is for in the static inline void fbuffer_inc_capa... declaration, it’s a way to tell the compiler that it would be

a good idea to inline this function. But that’s all it is, just a compiler hint, the compiler can still decide that you are wrong and that it knows better.

I don’t know the intricacies of LLVM/clang enough to know for certain why it decided to no longer inline all these functions, but I guessed that it

was because I made fbuffer_inc_capa much larger.

The reason it’s important fbuffer_inc_capa is inlined, is because 99%+ of the time, we return from it after just a very simple comparison:

RB_UNLIKELY(requested > fb->capa - fb->len). That’s the part we want inlined, so we don’t pay for a function call just for that check.

The rest of the function we don’t care so much, we rarely ever go into it.

So to appease the compiler, and make that conditional appealing to inline again, the solution would be to extract the large amount of code that is

rarely executed in another function that isn’t marked as inline:

static void fbuffer_do_inc_capa(FBuffer *fb, unsigned long requested)

{

// snip...

}

static inline void fbuffer_inc_capa(FBuffer *fb, unsigned long requested)

{

if (RB_UNLIKELY(requested > fb->capa - fb->len)) {

fbuffer_do_inc_capa(fb, requested);

}

}Running the benchmarks again with both changes, we finally had what we expected:

== Encoding small mixed (34 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 290.616k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 3.093M (± 0.3%) i/s (323.30 ns/i) - 15.693M in 5.073761s

Comparison:

before: 2829771.3 i/s

after: 3093060.4 i/s - 1.09x faster

== Encoding twitter.json (466906 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 208.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 2.088k (± 0.5%) i/s (479.01 μs/i) - 10.608k in 5.081469s

Comparison:

before: 2108.3 i/s

after: 2087.6 i/s - same-ish: difference falls within error

We squeezed a tiny bit more performance on the micro-benchmark, and the real work benchmark wasn’t noticeably impacted.

To Be Continued

At that point, with all the above optimizations, we were now faster than Oj when reusing the JSON::State object,

but still quite a bit slower when allocating it on every call:

== Encoding small mixed (34 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

json (reuse) 619.700k i/100ms

json 291.441k i/100ms

oj 532.966k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

json (reuse) 6.628M (± 4.9%) i/s (150.88 ns/i) - 33.464M in 5.064856s

json 3.191M (± 0.5%) i/s (313.35 ns/i) - 16.029M in 5.022818s

oj 5.873M (± 0.9%) i/s (170.26 ns/i) - 29.846M in 5.082087s

Comparison:

json (reuse): 6627811.3 i/s

oj: 5873337.3 i/s - 1.13x slower

json: 3191361.6 i/s - 2.08x slower

So there was no way around it, I had to find how to automatically re-use that JSON::State object. Or how to not allocate it at all?

But that’s a story for the next part.

-

In the initial version of this post I wrongly assumed the

asuffix was referring to “arrays of bytes”. Thanks to f33d5173 and ciupicri for lettingme know the real meaning on HN. ↩