Optimizing Ruby's JSON, Part 6

After wrapping up about the encoder optimizations in the previous post, we can now start talking about the parser side.

It certainly won’t be as long, because the parser didn’t need as much work, but also because some optimizations, particularly around setup costs were the same as the one applied to the encoder, so I will simply reference them quickly.

Efficient Hash Operations

When I took over the gem, there was a pull request by Luke Gruber that had been sitting there for almost a year, with multiple parser initialization speedups.

I mentioned the first one in part two,

the parser’s #initialize method was doing hash lookups in a very inefficient way by using rb_funcall to check if specific keys,

were present:

#define option_given_p(opts, key) RTEST(rb_funcall(opts, i_key_p, 1, key))I believe at one point using rb_funcall may have been necessary because opts, wasn’t always a real Hash,

but these days were long gone, so Luke was able to replace it with a much more efficient version:

static VALUE hash_has_key(VALUE hash, VALUE key)

{

if (Qundef == rb_hash_lookup2(hash, key, Qundef)) {

return Qtrue;

}

return Qfalse;

}

#define option_given_p(opts, key) (RTEST(hash_has_key(opts, key)))It is much much better as it doesn’t have to go through method lookup and all that.

Instead, it uses rb_hash_lookup2, the C equivalent of Hash#fetch. If key exists in the hash, the associated value

is returned. If it doesn’t exist, what we provided as a third argument is returned to us.

And Qundef is a special Ruby value, similar to undefined in JavaScript, but only used inside the virtual machine.

Actual Ruby code can’t possibly interact with Qundef, it would literally cause a VM crash.

As such we know it’s not possible for the hash to contain Qundef and we can use it as our return value in case of a miss.

So translated in Ruby, it would be something like:

UNDEF = BasicObject.new

private_constant :UNDEF

def hash_has_key(hash, key)

if hash.fetch(key, UNDEF) == UNDEF

return true

end

false

endAt that point, you may have been screaming internally for a few paragraphs, searching for how to submit a pull request on my blog to fix the typo, but no it’s not a typo, at least not on my part, the pull request indeed had the logic reversed. I admit I only noticed it while writing this post.

But that’s not a problem, because even aside from that bug, it still was a bit more contrived than necessary.

For some reason, it returns a Ruby boolean (Qfalse and Qtrue are global references to Ruby’s true and false

immediate objects, defined in special_consts.h).

Translated in decimal, it means we’re returning 0 when the key doesn’t exist, and 20 when it exists.

And then we use the RTEST macro, to check if the return value is 4 (Qnil), which is impossible, and if that’s the case we

turn that 4 into a 0, otherwise we return the original number.

To be fair, modern CPUs and compilers can chew through that sort of overhead, making it barely measurable, but it just felt wrong not to simplify it further.

Since the PR had to be rebased anyway, I simplified Luke’s version further to turn it into:

#define option_given_p(opts, key) (rb_hash_lookup2(opts, key, Qundef) != Qundef)Bail Out Early

Another important optimization that was in Luke’s pull request, was inside the code responsible for parsing floating point numbers.

JSON.parse has an option called decimal_class, which allows decimal numbers to be parsed into something other than Float objects,

typically into BigDecimal objects.

The float parsing code looked like this:

static char *JSON_parse_float(JSON_Parser *json, char *p, char *pe, VALUE *result)

{

// snipp...

VALUE mod = Qnil;

ID method_id = 0;

if (rb_respond_to(json->decimal_class, i_try_convert)) {

mod = json->decimal_class;

method_id = i_try_convert;

} else if (rb_respond_to(json->decimal_class, i_new)) {

mod = json->decimal_class;

method_id = i_new;

} else if (RB_TYPE_P(json->decimal_class, T_CLASS)) {

VALUE name = rb_class_name(json->decimal_class);

const char *name_cstr = RSTRING_PTR(name);

const char *last_colon = strrchr(name_cstr, ':');

if (last_colon) {

const char *mod_path_end = last_colon - 1;

VALUE mod_path = rb_str_substr(name, 0, mod_path_end - name_cstr);

mod = rb_path_to_class(mod_path);

const char *method_name_beg = last_colon + 1;

long before_len = method_name_beg - name_cstr;

long len = RSTRING_LEN(name) - before_len;

VALUE method_name = rb_str_substr(name, before_len, len);

method_id = SYM2ID(rb_str_intern(method_name));

} else {

mod = rb_mKernel;

method_id = SYM2ID(rb_str_intern(name));

}

}

// Actual float parsing starts here

long len = p - json->memo;

fbuffer_clear(json->fbuffer);

fbuffer_append(json->fbuffer, json->memo, len);

fbuffer_append_char(json->fbuffer, '\0');

if (method_id) {

VALUE text = rb_str_new2(FBUFFER_PTR(json->fbuffer));

*result = rb_funcallv(mod, method_id, 1, &text);

} else {

*result = DBL2NUM(rb_cstr_to_dbl(FBUFFER_PTR(json->fbuffer), 1));

}

return p + 1;

}Even if you are unfamiliar with C, with the comment I added you probably noticed that this routine has an insanely costly prelude.

We’re first checking if the decimal_class option responds to try_convert, then if it responds to new, and finally if it’s a Class

object. If you read part 2 of the series, you might remember that checking if an object responds to a method isn’t cheap.

But providing a custom class to handle decimal numbers is a niche option, certainly not the common case,

hence Luke’s patch rightfully wrapped all this decimal_class prelude into a cheap:

if (!NIL_P(jons->decimal_class)) {

// prelude

}To just bypass it all in the overwhelming majority of cases.

To be honest, the patch could have gone farther, as it really makes no sense for this code to be inside JSON_parse_float.

The decimal_class is provided when you instantiate the parser and isn’t ever going to change for the parser lifetime,

hence this argument parsing code should be in the constructor, not in a subroutine that will be called as many times as there are

decimal numbers in the parsed document.

As is often the case, this performance issue happened gradually.

In the early versions of the json gem, the check performed inside JSON_parse_float was a simple nil check:

if (NIL_P(json->decimal_class)) {

*result = rb_float_new(rb_cstr_to_dbl(FBUFFER_PTR(json->fbuffer), 1));

} else {

VALUE text;

text = rb_str_new2(FBUFFER_PTR(json->fbuffer));

*result = rb_funcall(json->decimal_class, i_new, 1, text);

}Translated in Ruby it would be:

if @decimal_class.nil?

@buffer.to_f

else

@decimal_class.new(@buffer)

endSo there was nothing to move to the constructor, it was as simple as a conditional as you could get.

But then over time the BigDecimal gem evolved, and BigDecimal.new was no longer a good way to instantiate these objects.

So in 2018, the maintainer of the bigdecimal gem submitted a patch to the json gem, to fix the deprecation warnings,

and the check became a bit more complex, but still very reasonable:

if (NIL_P(json->decimal_class)) {

*result = rb_float_new(rb_cstr_to_dbl(FBUFFER_PTR(json->fbuffer), 1));

} else {

VALUE text;

text = rb_str_new2(FBUFFER_PTR(json->fbuffer));

if (is_bigdecimal_class(json->decimal_class)) {

*result = rb_funcall(Qnil, i_BigDecimal, 1, text);

} else {

*result = rb_funcall(json->decimal_class, i_new, 1, text);

}

}Again, in Ruby:

if @decimal_class.nil?

@buffer.to_f

elsif @decimal_class == ::BigDecimal

BigDecimal(@buffer)

else

@decimal_class.new(@buffer)

endNow, when decimal_class isn’t nil, we’d also check if it is pointing to the BigDecimal class specifically.

Here again, really no concern, especially since most of the time we’d fall into the nil condition.

But then, in 2020, there was yet another iteration on that logic,

to make it more consistent with other parts of Ruby, and that’s where the check became way more expensive, and where the cheap

nil check that allowed to bail out early most of the time disappeared.

VALUE mod = Qnil;

ID method_id = 0;

if (rb_respond_to(json->decimal_class, i_try_convert)) {

mod = json->decimal_class;

method_id = i_try_convert;

} else if (rb_respond_to(json->decimal_class, i_new)) {

mod = json->decimal_class;

method_id = i_new;

} else if (RB_TYPE_P(json->decimal_class, T_CLASS)) {

VALUE name = rb_class_name(json->decimal_class);

const char *name_cstr = RSTRING_PTR(name);

const char *last_colon = strrchr(name_cstr, ':');

if (last_colon) {

const char *mod_path_end = last_colon - 1;

VALUE mod_path = rb_str_substr(name, 0, mod_path_end - name_cstr);

mod = rb_path_to_class(mod_path);

const char *method_name_beg = last_colon + 1;

long before_len = method_name_beg - name_cstr;

long len = RSTRING_LEN(name) - before_len;

VALUE method_name = rb_str_substr(name, before_len, len);

method_id = SYM2ID(rb_str_intern(method_name));

} else {

mod = rb_mKernel;

method_id = SYM2ID(rb_str_intern(name));

}

}

// snip...

if (method_id) {

VALUE text = rb_str_new2(FBUFFER_PTR(json->fbuffer));

*result = rb_funcallv(mod, method_id, 1, &text);

} else {

*result = DBL2NUM(rb_cstr_to_dbl(FBUFFER_PTR(json->fbuffer), 1));

}Which in Ruby would be:

mod = method = nil

if @decimal_class.respond_to?(:try_convert)

mod = @decimal_class

method = :try_convert

elsif @decimal_class.respond_to?(:new)

mod = @decimal_class

method = :new

elsif @decimal_class.is_a?(Class)

if @decimal_class.name.include?("::")

*namespace, name = @decimal_class.name.split("::")

mod = Object.const_get(namespace.join("::"))

method = name.to_sym

else

mod = Kernel

method = @decimal_class.name.to_sym

end

end

# snip...

if method

mod.send(method, @buffer)

else

@buffer.to_f

endSo quite a lot of logic.

To be clear, I’m absolutely not pointing fingers here, hindsight is 20/20 and I’m guilty of similar mistakes in the past. I just thought it was a good occasion to showcase how some code can become slower over time.

The code is initially simple and quite fast, and then it grows in complexity over time for perfectly legitimate reasons, with targetted patches that focus on a single function. Without an integrated benchmark suite, it’s very easy to merge changes without realizing their performance impact, especially since you often review a diff, without necessarily paying too much attention to where it is located.

Eliding Option Hash Allocation

Soon after rebasing Luke’s patches, I improved the setup cost further using similar techniques as for the generator.

The JSON.parse method used to be defined as:

def parse(source, opts = {})

Parser.new(source, **(opts||{})).parse

endThis means we always allocate an option Hash, even when no option was passed, and then splat it for little benefits.

By rewriting it as:

def parse(source, opts = nil)

if opts.nil?

Parser.new(source).parse

else

Parser.new(source, opts).parse

end

endI managed to get rid of a useless allocation.

Similarly, the JSON.load method, used to be:

def load(source, proc = nil, options = {})

opts = load_default_options.merge options

if source.respond_to? :to_str

source = source.to_str

elsif source.respond_to? :to_io

source = source.to_io.read

elsif source.respond_to?(:read)

source = source.read

end

if opts[:allow_blank] && (source.nil? || source.empty?)

source = 'null'

end

result = parse(source, opts)

recurse_proc(result, &proc) if proc

result

endWhich I optimized into:

def load(source, proc = nil, options = nil)

opts = if options.nil?

load_default_options

else

load_default_options.merge(options)

end

unless source.is_a?(String)

if source.respond_to? :to_str

source = source.to_str

elsif source.respond_to? :to_io

source = source.to_io.read

elsif source.respond_to?(:read)

source = source.read

end

end

if opts[:allow_blank] && (source.nil? || source.empty?)

source = 'null'

end

result = parse(source, opts)

recurse_proc(result, &proc) if proc

result

endFirst to avoid a Hash allocation when no option is passed,

and also to avoid calling respond_to? on the most common case, which is where source is a String.

It also saved a useless String#to_str call in that common case.

This is very similar to the optimizations performed in earlier parts so I won’t repeat here why this is preferable.

More Stack Allocation

Similarly, another optimization I directly ported from the encoding code, was to allocate some structures on the stack.

The ruby/json parser uses a small buffer for some operations, such as parsing numbers.

The underlying Ruby APIs the parser uses for that are rb_cstr_to_dbl and rb_cstr2inum.

These APIs, as indicated by their name, expect “C strings” (cstr), in other words, NULL terminated strings, which

isn’t very convenient in this context, as the numbers we’re interested in parsing are generally immediately followed by

the remainder of the JSON document, likely a comma or some other delimiter.

Hence, we have no choice but to first copy the string representation of the number into a separate buffer, add the NULL

terminator and then invoke the function provided by Ruby.

At this point, you are probably already thinking that this is wasteful and that it would be better to parse these numbers in place, but we’ll come back to it in the next post.

In the meantime, a simple fix was to allocate that internal buffer on the stack as we did with the generator saving us a pair

of malloc/free calls.

First by allocating the FBuffer structure on the stack,

then also allocating the internal buffer there as well. But that too we discussed at length in previous parts, so I won’t spend

too many words on it.

String Unescape

The previous optimizations were either old pull requests I rebased, or optimizations that were ported from the encoding code path, so they were basically no-brainers.

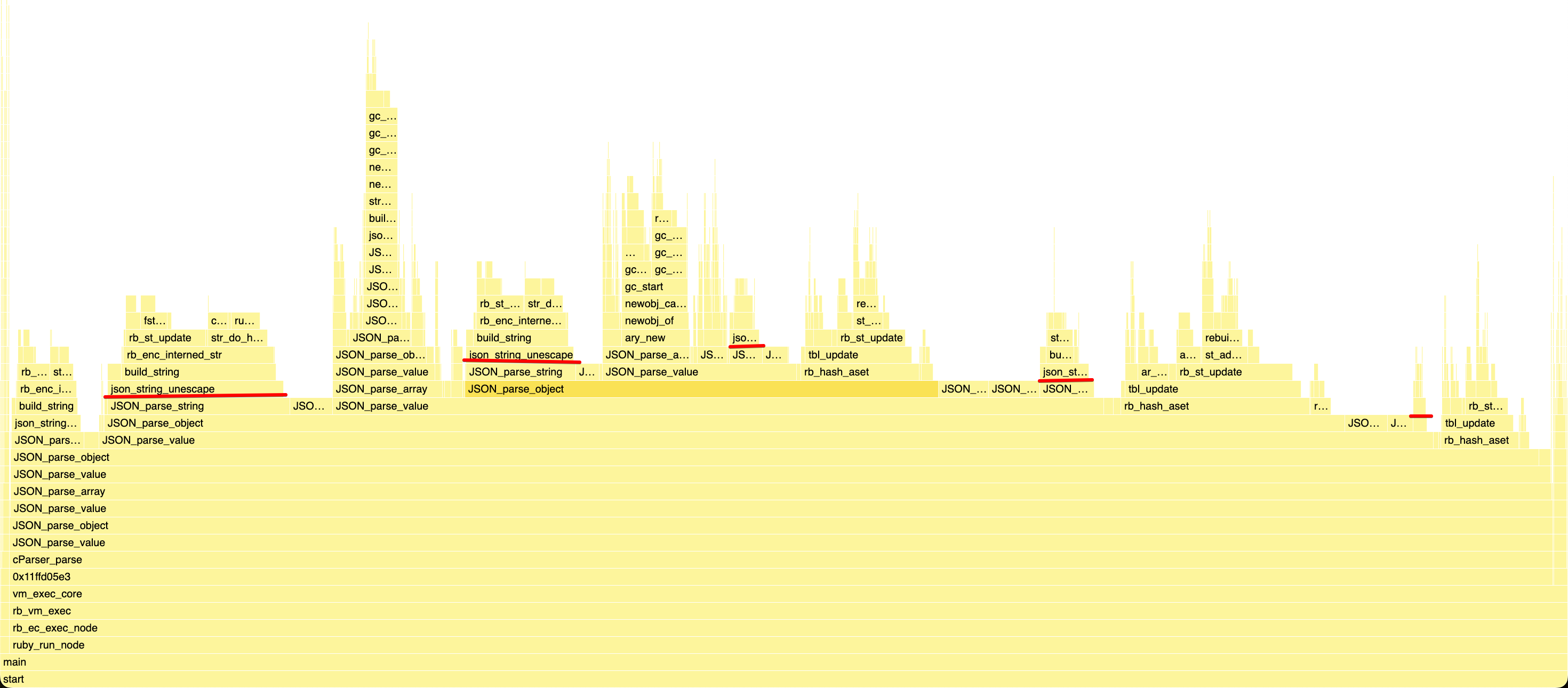

After that, I went on profiling macro-benchmarks, especially twitter.json.

Not so surprisingly, the most obvious hotspot was json_string_unescape, totaling over 23% of the overall runtime.

We’ll come back quite a few times to that function, so I’ll start by copying its initial version here and describe what it does.

static const size_t MAX_STACK_BUFFER_SIZE = 128;

static VALUE json_string_unescape(char *string, char *stringEnd, int intern, int symbolize)

{

VALUE result = Qnil;

size_t bufferSize = stringEnd - string;

char *p = string, *pe = string, *unescape, *bufferStart, *buffer;

int unescape_len;

char buf[4];

if (bufferSize > MAX_STACK_BUFFER_SIZE) {

bufferStart = buffer = ALLOC_N(char, bufferSize ? bufferSize : 1);

} else {

bufferStart = buffer = ALLOCA_N(char, bufferSize ? bufferSize : 1);

}

while (pe < stringEnd) {

if (*pe == '\\') {

unescape = (char *) "?";

unescape_len = 1;

if (pe > p) {

MEMCPY(buffer, p, char, pe - p);

buffer += pe - p;

}

switch (*++pe) {

case 'n':

unescape = (char *) "\n";

break;

case 'r':

unescape = (char *) "\r";

break;

case 't':

unescape = (char *) "\t";

break;

case '"':

unescape = (char *) "\"";

break;

case '\\':

unescape = (char *) "\\";

break;

case 'b':

unescape = (char *) "\b";

break;

case 'f':

unescape = (char *) "\f";

break;

case 'u':

if (pe > stringEnd - 4) {

if (bufferSize > MAX_STACK_BUFFER_SIZE) {

ruby_xfree(bufferStart);

}

raise_parse_error("incomplete unicode character escape sequence at '%s'", p);

} else {

uint32_t ch = unescape_unicode((unsigned char *) ++pe);

pe += 3;

/* To handle values above U+FFFF, we take a sequence of

* \uXXXX escapes in the U+D800..U+DBFF then

* U+DC00..U+DFFF ranges, take the low 10 bits from each

* to make a 20-bit number, then add 0x10000 to get the

* final codepoint.

*

* See Unicode 15: 3.8 "Surrogates", 5.3 "Handling

* Surrogate Pairs in UTF-16", and 23.6 "Surrogates

* Area".

*/

if ((ch & 0xFC00) == 0xD800) {

pe++;

if (pe > stringEnd - 6) {

if (bufferSize > MAX_STACK_BUFFER_SIZE) {

ruby_xfree(bufferStart);

}

raise_parse_error("incomplete surrogate pair at '%s'", p);

}

if (pe[0] == '\\' && pe[1] == 'u') {

uint32_t sur = unescape_unicode((unsigned char *) pe + 2);

ch = (((ch & 0x3F) << 10) | ((((ch >> 6) & 0xF) + 1) << 16)

| (sur & 0x3FF));

pe += 5;

} else {

unescape = (char *) "?";

break;

}

}

unescape_len = convert_UTF32_to_UTF8(buf, ch);

unescape = buf;

}

break;

default:

p = pe;

continue;

}

MEMCPY(buffer, unescape, char, unescape_len);

buffer += unescape_len;

p = ++pe;

} else {

pe++;

}

}

if (pe > p) {

MEMCPY(buffer, p, char, pe - p);

buffer += pe - p;

}

result = build_string(buffer, bufferStart, intern, symbolize);

if (bufferSize > MAX_STACK_BUFFER_SIZE) {

ruby_xfree(bufferStart);

}

return result;

}The function receives a start and end pointers, in other words, a read-only slice of bytes, and then simply two minor boolean parameters indicating whether the parsed string should be interned or cast to a symbol, but we can easily ignore that part.

At the beginning of it, the function allocates a dedicated buffer, if the string to unescape is 128B or less, the buffer is

allocated on the stack using alloca, or if it’s bigger, on the heap using malloc.

The function then scans the original string, byte by byte in search of backslash characters, once one is found, all the

scanned bytes until then are copied over in the buffer using memcpy, and then based on which characters follow the backslash,

the unescaped version of it is appended to the buffer, and then it goes back to search for the next backslash.

Once the entire source string has been scanned, the remaining bytes are copied with memcpy, and the Ruby String is built using

the buffer as a source, and finally the buffer is freed.

A Note on SIMD

One thing to note here is that the function tries to avoid the naive solution of copying bytes one by one right after having

scanned them, and instead try to do it in batches using memcpy (which appears as __platform_memmove in profiles).

This is because, while the implementation of memcpy is platform-specific, most implementations

leverage SIMD registers to copy blocks of 16, 32, or more bytes in one CPU instruction, which is massively faster. So that’s good.

If you are unfamiliar with what SMID is, I’ll try a simple explanation. Imagine you have a string, and you need to check if it is ASCII only or not, the naive implementation would be (using Ruby for clarity):

def ascii_only?(string)

string.each_byte do |byte|

if (byte & 0x80) > 0 # 0x80 == 0b10000000

return false

end

end

true

endIt’s quite straightforward, you go over bytes in the string one by one, and for each apply a bitmask (0x80) to validate

it’s in the ASCII range, because ASCII characters are in the 0..127 range, so in binary form, it means only the 7 least

significant bits can be set in each byte.

But that’s a bit wasteful, as for each byte we need to:

- Load the byte in a register.

- Apply the bitwise AND.

- Conditionally jump.

- Increment the for loop counter.

- Another conditional jump to go back at the beginning of the loop.

Even if you ignore the relative cost of each of these steps, you can see that the actual operation we want to perform, the bitwise AND and the conditional jump, is entirely dwarfed by the work necessary to perform the looping. That’s about only 2 out of 5 instructions.

But there’s a fairly well-known way to make this about 8 times faster on 64-bit processors, by checking the bytes in chunks of 8 instead of one by one:

def ascii_only?(string)

string.unpack("Q*C*").each do |unsigned_int_64|

if (unsigned_int_64 & 0x8080808080808080) > 0

return false

end

end

true

endSince a character is just one byte, and a processor register can hold 8 bytes (64-bit), you can load 8 characters in a

single register, and apply the same bitmask to all of the 8 bytes at once, by simply repeating the 0x80 pattern, which

drastically the ratio of useful instructions, and the number of times you have to loop.

Well, SIMD, which stands for Single Instruction Multiple Data, is exactly that idea, pushed further, with some even larger registers, and a wider set of specialized instructions to more easily work on what are essentially small arrays. You may have heard it referred to as vectorization. Some modern processors have SIMD registers as large as 512 bits, enough to copy or process 64 characters at once.

The downside however is that different processors have different APIs, so if you want to support both x86_64 processors and ARM64 processors, you need to write two versions of your routine, and probably a third version not using SIMD as a fallback. And even if you only support x86_64, older or lower-end processors will only have older API, for instance depending on how old of an Intel CPU you want to support you might need an SEE, SSE2, SSE3, SSSE3, SSE4.x, AVX, AVX2 and AVX-512 implementation, and as I’m writing this, Intel as announced the future AVX10 instruction set.

And you don’t just need to write multiple versions, you also need some extra code to detect which CPU you’re running on and dynamically select the best usable implementation.

So SIMD is very powerful, but it’s a ton of work to use it on multi-platform C code, too much work for me to consider

maintaining that in ruby/json.

Be Optimistic

Now that we said all that, what can we do to speed up json_string_unescape? As always the key is to start focusing on the

happy path. We can easily assume most strings in a JSON document don’t need to be escaped. If we use twitter.json as an

example, some of the tweet bodies contain newline characters (\n), and then their source property contains some HTML,

hence having a few escaped double quotes. Other than that, none of the other strings need to be unescaped.

In those cases, the current implementation is quite wasteful, we scan bytes one by one, copy them all into a buffer, and then ask Ruby to copy the content again inside a Ruby String. If the overwhelming majority of strings don’t need to be escaped, we can avoid one copy, and one buffer allocation and deallocation.

So the idea is to wait until we’ve found the first backslash until we concern ourselves with allocating a buffer.

You can look at the full patch

(if you do ignore the parser.c file which is machine-generated from parser.rl), but the crux of it is just 4 lines

added at the top of json_string_unescape:

pe = memchr(p, '\\', bufferSize);

if (RB_LIKELY(pe == NULL)) {

return build_string(string, stringEnd, intern, symbolize);

}Here I used memchr, which is a function that’s part of the C standard library (like memcpy), used to search for one

character in a string, that’s something that is the ideal use case for SIMD. So it depends on which libc is used in the end,

but there’s a very high chance it is optimized to use SIMD, without ruby/json needing to do the extra work.

The result of just that small change was pretty good:

== Parsing twitter.json (567916 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 60.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 603.730 (± 0.2%) i/s (1.66 ms/i) - 3.060k in 5.068496s

Comparison:

before: 552.0 i/s

after: 603.7 i/s - 1.09x faster

Given that json_string_unescape was profiled as 23% of overall runtime, getting a 9% speedup overall from just optimizing

that one function is huge, close to a 2x improvement.

Reuse Buffers

My next idea to improve json_string_unescape, was that when we’re not in the happy path, rather than use a stack or heap

buffer to do the unescaping, which we then have to copy a second time, we might as well work directly inside Ruby-owned memory,

by using the Ruby string we’ll end up returning as our intermediary buffer.

As I mentioned previously, Ruby strings can be hard to use as dynamic buffers from C, because if you need to resize them, you have to be very careful as to how the GC could react.

But in this case, we’re unescaping JSON, so we know upfront that the final unescaped string won’t possibly be larger than the original escaped one, so we know we won’t need to resize the string.

You can look at the full patch, but the crux of it is again at the top of

json_string_unescape:

VALUE result = rb_str_buf_new(bufferSize);

rb_enc_associate_index(result, utf8_encindex);

buffer = bufferStart = RSTRING_PTR(result);Since our more realistic benchmarks don’t have that many strings that need escaping, the difference there isn’t very big, but by crafting a dedicated micro-benchmark, we can see it more easily:

benchmark_parsing "lots_unescape", JSON.dump(["\n"*200]*100)== Parsing lots_unescape (40301 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 1.809k i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 18.048k (± 0.3%) i/s (55.41 μs/i) - 90.450k in 5.011607s

Comparison:

before: 16591.5 i/s

after: 18048.3 i/s - 1.09x faster

And in general, even if something doesn’t help the happy path, hence doesn’t move the needle much on macro-benchmark, it’s still good not to neglect the performance of the unhappy path.

Elide Parser Allocation

The next optimization I performed, was another direct port of a previous optimization from the generator.

If you remember the JSON.parse method:

def parse(source, opts = nil)

if opts.nil?

Parser.new(source).parse

else

Parser.new(source, opts).parse

end

endYou can see we instantiate a JSON::Parser instance, but immediately discard it after having called a method on it.

Using more pompous terms, the Parser instance doesn’t escape the parse method.

As such we can entirely skip on allocating that object, like we did with the JSON::State instance, but it’s even simpler

as we don’t even need logic to allocate it on the fly as it is never needed.

Sufficiently advanced compilers can perform this sort of optimization on their own, that’s what they refer to as “escape analysis”, and that is how some JITs can sometimes actually reduce memory usage of an application, by automatically eluding some allocations. Here however it would be very hard for a compiler to perform as it would need to understand both the Ruby and C parts of the program, perhaps older versions of TruffleRuby would have been able to optimize this out when they used to interpret C extensions, but I’m not sure.

You can look at the full patch, which shipped with a few other optimizations like the more efficient way to process option hashes, but nothing we haven’t talked about before, so let’s move on.

Caching Parsed Objects

At that point, JSON.parse was getting really close to alternatives on macro benchmarks,

but I didn’t have any immediate ideas on what to do to go beyond that:

== Parsing twitter.json (567916 bytes)

ruby 3.3.4 (2024-07-09 revision be1089c8ec) +YJIT [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

json 57.000 i/100ms

oj 62.000 i/100ms

Oj::Parser 78.000 i/100ms

rapidjson 56.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

json 573.527 (± 1.6%) i/s (1.74 ms/i) - 2.907k in 5.070094s

oj 619.368 (± 1.6%) i/s (1.61 ms/i) - 3.100k in 5.006550s

Oj::Parser 770.095 (± 0.9%) i/s (1.30 ms/i) - 3.900k in 5.064768s

rapidjson 560.601 (± 0.4%) i/s (1.78 ms/i) - 2.856k in 5.094597s

Comparison:

json: 573.5 i/s

Oj::Parser: 770.1 i/s - 1.34x faster

oj: 619.4 i/s - 1.08x faster

rapidjson: 560.6 i/s - 1.02x slower

Surely we should be able to match Oj.load, given it has a similar interface, but beating Oj::Parser wasn’t realistic

because it had a major inherent advantage, its statefulness:

Benchmark.ips do |x|

x.report("json") { JSON.parse(json_output) } if RUN[:json]

x.report("oj") { Oj.load(json_output) } if RUN[:oj]

x.report("Oj::Parser") { Oj::Parser.usual.parse(json_output) } if RUN[:oj]

x.report("rapidjson") { RapidJSON.parse(json_output) } if RUN[:rapidjson]

x.compare!(order: :baseline)

endOj::Parser.usual always returns the same Oj::Parser instance, and it has a few internal caches.

For instance, it caches the parsed Hash keys, so that if the same key is encountered more than once, it is only allocated once.

This is made easy by Ruby, because not many people know this, but when you use a string as a hash key, it often doesn’t use the key you gave it, but makes a copy:

# frozen_string_literal: true

hash = {}

key = "my_key"

key_copy = key.dup

hash[key_copy] = 1

hash.keys.first.equal?(key_copy) # => false

hash.keys.first.equal?(key) # => true

hash.keys.first.frozen? # => trueThe reason is that hashes behave quite weirdly when their keys are mutated. Ruby lets you do it with other types, but given strings are among the most common hash keys, they are treated a bit differently, in pseudo-Ruby, the logic would be something like:

class Hash

def []=(key, value)

if entry = find_entry(key)

entry.value = value

else

if key.is_a?(String) && !key.interned?

if interned_str = ::RubyVM::INTERNED_STRING_TABLE[key]

key = interned_str

elsif !key.frozen?

key = key.dup.freeze

end

end

self << Entry.new(key, value)

end

end

endSo when inserting into a Hash, if the key is a String, and isn’t interned, Ruby will first try to check if an equivalent string has been interned. And if that’s the case, it replaces the provided key with its interned counterpart.

If there is no equivalent interned string, then it checks if the provided key is frozen, if it isn’t, it makes a copy and freezes it.

So it’s impossible to have a mutable String as a hash key, and if you insert something in a hash using a mutable string as a key, that will likely cause an extra allocation.

That’s why when parsing some format into a hash, it’s a good idea to pre-freeze string keys, as it can reduce allocations quite significantly.

But beyond just pre-freezing, you can also pre-intern the string, which is something I added a while ago to the JSON gem, long before I was a maintainer, using a set of Ruby C APIs I added back in Ruby 3.0. When using Ruby-level APIs, if you are parsing something and wish to intern a string, you can’t elude the allocation, because you need to build a string to be able to look up the interned strings table, so it’s some sort of chicken and egg problem. But these APIs allow to “find or create” an interned Ruby String, directly from a raw C string with only 0 or 1 allocation.

The way they do it is by allocating what’s referred to as a “fake string” on the stack and using that to look up the table. If it’s a hit, then it returns the existing heap object it found, if not, it spills the “fake string” on the heap and intern it.

If you are curious about it, you can look at rb_interned_str, setup_fake_str and register_fstring in string.c,

but the crux of it is here:

static VALUE

setup_fake_str(struct RString *fake_str, const char *name, long len, int encidx)

{

fake_str->basic.flags = T_STRING|RSTRING_NOEMBED|STR_NOFREE|STR_FAKESTR;

if (!name) {

RUBY_ASSERT_ALWAYS(len == 0);

name = "";

}

ENCODING_SET_INLINED((VALUE)fake_str, encidx);

RBASIC_SET_CLASS_RAW((VALUE)fake_str, rb_cString);

fake_str->len = len;

fake_str->as.heap.ptr = (char *)name;

fake_str->as.heap.aux.capa = len;

return (VALUE)fake_str;

}

VALUE

rb_interned_str(const char *ptr, long len)

{

struct RString fake_str;

return register_fstring(setup_fake_str(&fake_str, ptr, len, ENCINDEX_US_ASCII), true, false);

}You can notice I didn’t make the “fake string” name up, it’s right there in the STR_FAKESTR flag.

Given all the above, if you expect a hash key to appear multiple times, it can be a good idea to pre-intern it yourself, and to keep it handy, so that you save on further hash lookups.

That’s something Oj::Parser can more easily do, because its API is stateful, you allocate a parser object, and use it multiple

times, which allows it to keep state around, cache immutable objects and re-use them. It’s not all rainbows and unicorns though, if you have some

mutable state, you have to worry about concurrent access. Generally, that means you have to synchronize a mutex whenever you access

that state, which isn’t good for performance, or simply state the API isn’t thread safe and each thread should have its own parser

object. It also means you have to concern yourself with cache eviction, as the parser may be used to parse radically different

documents, so you need to keep track of how often keys are used and get rid of the cold ones. That’s a lot of extra logic so it’s

not guaranteed at all to pay off.

In ruby/json’s case, I wanted to make the already existing JSON.parse API faster, not expose a new faster one, so this sort

of persistent cache isn’t a great fit. But that doesn’t mean the general idea couldn’t be adapted.

Having a persistent cache makes a huge difference on micro-benchmarks, so in a way, it would be nice, but it really isn’t as big of a deal on more real-world workloads, at least not most of them, unless you have lots of parser instances and you always re-use the same instance to parse the same JSON schemas.

But if you look at the macro-benchmarks in ruby/json, a lot of them have a similar structure, it’s one big array of objects with

all the same keys:

[

{

"name": "...",

"src": "https://...",

...

},

{

"name": "...",

"src": "https://...",

...

},

...

]And that shouldn’t be a surprise, because that’s one of the biggest use cases for parsing JSON documents, REST APIs, GraphQL, etc.

With such a structure being expected to be common, even a cache that doesn’t escape the JSON.parse method could improve performance.

And if we’re not sharing the cache between documents, we don’t need to bother with synchronization or concurrent accesses,

don’t even really need to bother with evictions, and can probably afford it being relatively smaller. Small enough that it would

safely fit on the stack?

Since I liked the idea, I figured I might as well lean all the way into it. The kinda go-to data structure to use for caches is some form of hash table, or binary tree. But these structures have lots of references, they don’t make the best use of limited memory space.

That’s where I started remembering Aaron’s work on Ruby’s object shapes lookup cache, for which he used a cool data structure: Red Black Trees. I’m not going to go into too much detail about those, because Aaron did multiple talks on them recently, for instance his keynote at Tropical.rb, and he explains them extremely well.

But in short, it’s a tree structure that offers a good O(log n) search and insertion performance and doesn’t require that much

overhead on top of the useful payload. Each tree node needs one bit to store the color and two references to child nodes on top

of holding one entry. By packing structs efficiently, this could be done with just 16B per entry, so pretty good.

But as I was implementing it, I realized it was a lot of complexity for a cache I intended to be very small, a few dozen, certainly less than a hundred entries. And when dealing with a very small amount of data, algorithm complexity isn’t always the best predictor of performance.

So I figured I’d first try with what’s probably part of Computer Science 1011: a good old binary search.

If you think about it, doing a binary search in a sorted array has the same O(log n) complexity, but it’s also much more compact.

The one big downside is that during insertion you might need to move some elements, so it’s potentially O(n),

but since we know we’ll be using a small array, it means not a lot of data to move, and since we’re not considering evictions,

we’ll fairly quickly stop inserting.

So most of the downsides of that solution don’t fully apply here, and being more compact is good given we want to use the stack to store it, and it plays well with CPU caches and such, no pointer chasing or anything. In the worst case, if it didn’t perform well, I could easily swap it for another data structure, and the interface would remain the same.

You can have a look at the full patch, there’s not a whole lot I feel I can explain about it.

The only few key details are that I settled for a cache size of 63 entries and that strings longer than 55B aren’t considered

for caching. Both of those are somewhat eye-balled heuristics of when it’s no longer worth trying to use the cache:

#define JSON_RSTRING_CACHE_CAPA 63

#define JSON_RSTRING_CACHE_MAX_ENTRY_LENGTH 55

typedef struct rstring_cache_struct {

int length;

VALUE entries[JSON_RSTRING_CACHE_CAPA];

} rstring_cache;This immediately yielded a nice 15% improvement on the activitypub.json and twitter.json benchmarks:

== Parsing twitter.json (567916 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 70.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 708.951 (± 0.6%) i/s (1.41 ms/i) - 3.570k in 5.035785s

Comparison:

before: 617.3 i/s

after: 709.0 i/s - 1.15x faster

But they’re exactly the kind of documents I had in mind, so somewhat expected. What was less good, however, is that another macro-benchmark was impacted, but negatively:

== Parsing citm_catalog.json (1727030 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 30.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 303.890 (± 0.3%) i/s (3.29 ms/i) - 1.530k in 5.034746s

Comparison:

before: 323.8 i/s

after: 303.9 i/s - 1.07x slower

That I didn’t like, so I started to investigate.

It turned out that citm_catalog.json was the key cache’s worst nightmare:

{

"areaNames": {

"205705993": "Arrière-scène central",

// 15 more unique keys

"342752287": "Zone physique secrète"

},

"audienceSubCategoryNames": {

"337100890": "Abonné"

},

"blockNames": {},

"events": {

"138586341": {

"description": null,

"id": 138586341,

"logo": null,

"name": "30th Anniversary Tour",

"subTopicIds": [

337184269,

337184283

],

"subjectCode": null,

"subtitle": null,

"topicIds": [

324846099,

107888604

]

},

"138586345": {

"description": null,

"id": 138586345,

// snippIt does have a lot of repeated keys like we expect many JSON documents to have, however, it happens to also have many numeric keys, likely internal database IDs, and since JSON only supports strings as object keys, they’re all represented as strings, and these aren’t repeated much and fill the cache with junk almost immediately.

Even though the gain on twitter.json and activitypub.json was much bigger than the loss on citm_catalog.json,

that didn’t feel great, and that annoyed me a lot.

After some reflection, I figured the idea behind this optimization was to help with JSON objects that are essentially

tables rows, citm_catalog.json was mostly one, but mixed with some references.

Based on this, It seemed fair game to all keys that don’t look like a “column” name, such as the one starting with a digit,

so I added one little check:

if (RB_UNLIKELY(!isalpha(str[0]))) {

// Simple heuristic, if the first character isn't a letter,

// we're much less likely to see this string again.

// We mostly want to cache strings that are likely to be repeated.

return rb_str_freeze(rb_utf8_str_new(str, length));

}With that extra little check, the 7% loss turned into a 15% gain:

== Parsing citm_catalog.json (1727030 bytes)

ruby 3.4.1 (2024-12-25 revision 48d4efcb85) +YJIT +PRISM [arm64-darwin23]

Warming up --------------------------------------

after 36.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

after 369.793 (± 0.3%) i/s (2.70 ms/i) - 1.872k in 5.062369s

Comparison:

before: 321.7 i/s

after: 369.8 i/s - 1.15x faster

I know it might sound like benchmark gaming, but this whole optimization is based on heuristics that I really think holds

true for a very large number of documents parsed with ruby/json, and it’s not that different from the cap on 55B strings.

Later on, I went further with heuristics for when the cache should and shouldn’t be used, notably by skipping it if we’re not currently parsing an array:

{

"not_worth_caching": 1,

"items": [

{

"worth_caching": {

"also_worth_caching": 2

}

}

]

}You can see the followup patch here.

To Be Continued

I have about three more parser optimizations to talk about, and after that, I think this series will be finally done, unless I talk about other things JSON, like my ideas for the future, or some thoughts on what I think isn’t good in its current API, but we’ll see.

Edit: Part 7 is here.

-

Actually I have no idea what’s in Computer Science 101. ↩